Narcissism

The Two Faces of Feminism: Grandiose and vulnerable

Narcissism among self-identified feminists has been studied by Imogen Tyler in her paper ‘Who put the “Me” in feminism?’ The sexual politics of narcissism (2005), which surveyed the connection between feminism and narcissism that has long been a subject of public discourse, and a more recent study has confirmed that feminist women have significantly higher levels of narcissism than non-feminist women, and are less tolerant of disagreement than non-feminist women (Taneja & Goyal, 2019).

Narcissism may be expressed in grandiose or vulnerable ways, and empirical studies confirm that these two modalities work as “two sides of the same coin” (Sar & Türk-Kurtça, 2021) with narcissistic individuals typically oscillating, Janus faced, between these subtypes. Likewise, feminist behaviour displays features of both vulnerable or grandiose narcissism, along with oscillations between these two modes of expression.

As detailed by Naomi Wolf, feminism tends to bifurcate along grandiose and vulnerable lines, or what she refers to as “power” and “victim feminism” (Wolf, 2013). Wolf explains that victim feminism is when a woman seeks power through an identity of disenfranchisement and powerlessness, and adds that this amounts to a kind of “chauvinism” that is not confined to the women’s movement alone, stating; “It is what all of us do whenever we retreat into appealing for status on the basis of feminine specialness instead of human worth, and fight underhandedly rather than honourably.” (Wolf, p147. 2013).

Wolf adds that the deluded rhetoric of the victim-feminist creates, “a dualism in which good, post-patriarchal, gynocentric power is ‘personal power,’ to be distinguished from ‘the many forms of power over others.’” (Wolf, p160. 2013). Other feminist writers have independently concurred with Wolf’s categorisation of ‘agentic’ and ‘victim’ modes of performing feminism (Wolf, 2013; Denfeld, 2009; Sommers, 1995; Roiphe, 1993).

A century prior to observations made by Wolf, English philosopher E. Belfort Bax observed the same bifurcation within first wave feminism, describing a grandiose form of activism he referred to as ‘political feminism’ which concerned itself with claiming equal rights and privileges for women without demonstrating commensurate achievements, capabilities, responsibilities or sacrifices with men, and secondly a vulnerable kind he called ‘sentimental feminism’ which concerned itself with securing sympathies toward women while at the same time fostering antipathy toward men. Bax made the observation that these two forms of activism often occurred in individual feminists who would oscillate between these modes of expression depending on which one was momentarily efficacious for securing power. (Bax, 1913).

References:

Bax, E. B. (1913). The Fraud of Feminism. Grant Richards.

Denfeld, R. (2009). The new Victorians: A young woman’s challenge to the old feminist order. Hachette UK.

Roiphe, K. (1993). The morning after: Fear, sex, and feminism on college campuses. Boston, Mass.

Sar, V., & Türk-Kurtça, T. (2021). The vicious cycle of traumatic narcissism and dissociative depression among young adults: A trans-diagnostic approach. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 22(5), 502-521.

Sommers, C. H. (1995). Who stole feminism?: How women have betrayed women. Simon and Schuster

Taneja, S., & Goyal, P. (2019). Impact of Feminism on Narcissism and Tolerance for Disagreement among Females. Indian Journal of Mental Health, 6(1).

Tyler, I. (2005). ‘Who put the “Me” in feminism?’ The sexual politics of narcissism. Feminist Theory, 6(1), 25-44.

Wolf, N. (2013). Fire with fire: New female power and how it will change the twenty-first century. Random House.

Gynocentrism and female narcissism

The following articles explore the role of narcissism in the context of gynocentric culture & behaviour. This emphasis is not aimed to reduce narcissism to an all-female pathology, but to demonstrate the ways in which female narcissism may lean toward gynocentric modes of expression, much as males demonstrate narcissism in typically gendered ways.

Formal studies in female narcissism by Ava Green (and colleagues) :

-

- Perceptions of female narcissism in intimate partner violence: A thematic analysis (2019)

- Voicing the victims of narcissistic partners: A qualitative analysis of responses to narcissistic injury and self-esteem regulation (2019)

- Unmasking gender differences in narcissism within intimate partner violence (2020)

- Gender differences in the expression of narcissism: Diagnostic assessment, aetiology, and intimate partner violence perpetration (2020)

- Recollections of parenting styles in the development of narcissism: The role of gender (2020)

- Female Narcissism: Assessment, Aetiology, and Behavioural Manifestations (2021)

- Clinician perception of pathological narcissism in females: a vignette-based study (2023)

- Mean Girls in Disguise? Associations Between Vulnerable Narcissism and Perpetration of Bullying Among Women (2024)

- Gendering Narcissism: Different Roots and Different Routes to Intimate Partner Violence (2024)

- Narcissism: it’s less obvious in women than in men – but can be just as dangerous (2024)

- Gender bias in assessing narcissistic personality: Exploring the utility of the ICD-11 dimensional model (2024)

- ‘The Way In Which Narcissistic Women Abuse Is More Likely Overlooked’ – An interview with psychologist Dr Ava Green (2025)

Articles on gynocentrism & narcissism by Peter Wright:

- A. Kostakis & P. Wright – Is gynocentrism a narcissistic pathology? (2011)

- Cornelius Castoriadis: The Narcissistic Social Contract (2014)

- Gynocentrism as a Narcissistic Pathology – Part 1 (2020)

- Gynocentrism as a Narcissistic Pathology – Part 2 (2023)

- Narcissism Exaggerates Baseline Hypergamy (2023)

- Does female narcissism involve any kind of moral responsibility? (2023)

- Vulnerable Narcissism And The Tendency For Interpersonal Victimhood (2023)

- The Two Faces of Feminism: Grandiose and vulnerable (2023)

- Romantic Chivalry Encourages Female Narcissism (2023)

- Gynocentric Economies Eventually Lead To Low Birth Rates (2024)

Articles on the narcissism ~ hypergamy conflation:

- Is It Really Hypergamy—Or Just Narcissism in Disguise? (2025)

- Narcissism vs. Hypergamy: A Comparative Analysis (Chat GPT 2025)

- Evolutionary & Sociological Definitions of Hypergamy: A Synthesized Definition (Chat GPT 2025)

- David Buss’s Hypergamy Theory May Be a Misinterpretation Of Modern Cultural Narcissism (2025)

Research on interrelationship of narcissism and feminism:

- Impact Of Feminism On Narcissism And Tolerance For Disagreement Among Females (2018)

- Evidence for the Dark-Ego-Vehicle Principle: Higher Pathological Narcissism Is Associated With Greater Involvement in Feminist Activism (2022)

- Evidence for the Dark-Ego-Vehicle Principle: Higher Pathological Narcissistic Grandiosity and Virtue Signaling are Related to Greater Involvement in LGBQ and Gender Identity Activism (2022)

Miscellaneous

- Narrative Transference and Female Narcissism: The Social Message of Adam Bede (2003)

- Mental Disorders of the New Millennium: Acquired Situational Narcissism (2006)

- Denis De Rougemont: Romantic Love is “Twin narcissism” (1939)

- Madame Bovary Syndrome (English Translation from the original French paper – 1892

- What Is Madame Bovary Syndrome? (2018)

- I want a man who will “spoil” me (2024)

Informal Articles

- When did getting married become an exercise in acquired situational narcissism? (2007)

- Paul Elam: Narcissism Isn’t Self-Esteem [satire piece]

- Chat GPT Details The Relation Between Gynocentrism & Narcissism (2023)

- Bing AI ‘CoPilot’ On The Relation Between Gynocentrism & Narcissism (2023)

- “Performative femininity” of tradwives may be a manifestation of narcissism (2025)

Narcissism Exaggerates Baseline Hypergamy

Many social media commentators discuss the rise of hypergamous behaviors among modern women. Some pose reasonable evolutionary hypotheses for such behavior, but there may be another cause at work – cultural narcissism.

Observations of extreme hypergamy among women may be equally explained by the rise of cultural narcissism in affluent societies (Twenge & Campbell, 2009), a motive that differs from baseline hypergamy, but which nevertheless involves comparable behaviors of self-enhancement and status-seeking.

Society’s encouragement of men in chivalric deference to women, and the associated practice of ‘placing women on a pedestal’, has generated a degree of gendered narcissism among women over time. To frame this differently, Acquired Situational Narcissism can arise with any acquired social status; for example in academic experts, politicians, pop singers, actors – and also in women who, in modern society, are taught that they deserve to be recognised for thier worth, dignity, value, purity, status, reputation and esteem in the context of their relationships with men. This psychological disposition in women, partly a result of traditional chivalry, promotes exaggerated self-enhancement behaviours beyond what evolutionary models of hypergamy would require.

Among narcissistic individuals, studies find higher incidence of hypergamy-like behaviors, indicating that such behavior is not the result of a culture of sexual liberation alone, nor of baseline evolutionary imperatives; it may also be the result of an acquired social class narcissism that says “I deserve.”

Excerpts from narcissism studies:

A third strand of evidence concerns narcissists’ relationship choices. Because humans are a social species, relationship choices are an important feature of situation selection. Narcissists are more likely to choose relationships that elevate their status over relationships that cultivate affiliation. For example, narcissists are keener on gaining new partners than on establishing close relationships with existing ones (Wurst et al., 2017). They often demonstrate an increased preference for high-status friends (Jonason & Schmitt, 2012) and trophy partners (Campbell, 1999), perhaps because they can bask in the reflected glory of these people. In sum, narcissists are more likely to select social environments that allow them to display their performances publicly, ideally in competition with others. These settings are potentially more accepting and reinforcing of narcissistic status strivings.

Source: The “Why” and “How” of Narcissism: A Process Model of Narcissistic Status Pursuit1

Consistent with the self-orientation model, Study 5 provided an empirical demonstration of the mediational role of self enhancement in narcissists’ preference for perfect rather than caring romantic partners. Furthermore, these potential romantic partners were more likely to be seen as a source of self-esteem to the extent that they provided the narcissist with a sense of popularity and importance (i.e., social status). Narcissists’ preference for romantic partners reflects a strategy for interpersonal self-esteem regulation. Narcissists also were attracted to self-oriented romantic partners to the extent that these others were viewed as similar. The mediational roles of self-enhancement and similarity were independent. That is, narcissists’ romantic preferences were driven both by a desire to gain self-esteem and a desire to associate with similar others.

Narcissism has been linked with the materialistic pursuit of wealth and symbols that convey high status (Kasser, 2002; Rose, 2007). This quest for status extends to relationship partners. Narcissists seek romantic partners who offer self- enhancement value either as sources of fawning admiration, or as human trophies (e.g., by possessing impressive wealth or exceptional physical beauty) (Campbell, 1999; Tanchotsrinon, Maneesri, & Campbell, 2007)

Source: The Handbook of Narcissism And Narcissistic Personality Disorders3

Narcissists are looking for partners who can provide them with self-esteem and status. How can a romantic partner provide status and esteem? First, he or she can do so directly: a romantic partner who admires me and thinks that I am wonderful elevates my esteem. Second, he or she can do so indirectly through a basic association: my partner is beautiful and popular, therefore I am too. This indirect esteem generation is clear from a range of social psychological research, from the self-evaluation maintenance (SEM) model (Tesser, 1988) to Basking in Reflected Glory (BIRGing; Cialdini et al., 1976). This indirect esteem provisioning is evident in the term “trophy” partner.

There is good empirical evidence that narcissists like targets who provide esteem and status both directly and indirectly (Campbell, 1999). There is also an important interaction effect. Namely, narcissists like popular and attractive partners, especially when those others admire them. Narcissists, however, are not particularly interested in admiration from just anybody. This finding is inconsistent with the “doormat hypothesis.” Narcissists are not looking for someone they can walk on and who worships them; rather, narcissists are looking for someone ideal who also admires them.

The next question, of course, is what characteristics of a potential partner make them able to provide narcissists with narcissistic esteem? Not surprisingly, what narcissists particularly look for in a partner are physical attractiveness and agentic traits (e.g., status and success). A narcissist’s ideal partner is like a narcissist’s ideal self (recall Freud’s comments): attractive, successful, and admiring of the narcissist. Indeed, in our research, narcissists report that part of the reason that they are drawn to attractive and successful partners is that these people are similar to them (Campbell, 1999).

Dozens more quotations could be added, however the point is obvious: self-enhancement strategies of both narcissism and hypergamy share overlapping features.

The rise of narcissistic behaviors among women is receiving increased attention from academia, particularly with the addition of new variants to the lexicon such as communal narcissism, and vulnerable narcissism, which appear to be preferred female modes of expressing narcissism. A more in-depth survey of narcissism variants among women, and their implications can be read here.

Hypergamy, as an evolutionary motivation, doesn’t require a woman to overestimate her own attractiveness and desirability as she seeks to secure high resource/status males. Narcissism, on the contrary, does entail an overestimation by women of their own attractiveness & desirability as they seek to secure high resource/status males.

To discover whether hypergamy or narcissism is at play, one might simply ask a woman to rate her own attractiveness. If she strongly overrates herself, then her mating-up is likely driven by narcissism and is maladaptive. If she rates herself honestly, then her desire to mate up is more likely driven by an adaptive hypergamy. Mating-up today appears largely driven by maladaptive narcissism; therefore any rationalizing or excusing it as “natural” and “adaptive” serves to compound and increase that same culturally-driven narcissism.

A note on terminology:

Sigmund Freud introduced narcissism as a developmental trait that ranged from healthy to unhealthy.5,6 Some evolutionary psychologists posit that a degree of narcissism might be adaptive in the wider evolutionary sense, though this hypothesis (which has zero genetic evidence to confirm it) can only be applied to a limited subset of behaviours before tipping into maladaptive expressions of narcissism as measured by the usual psychometric instruments.7,8,9 Moreover, no one has satisfactorily demonstrated that a mild, non-pathological narcissism is adaptive and belongs to a construct continuum with more pathological narcissism; therefore it is conjecture to claim that narcissism is natural, but that it simply “gets out of hand” at the more extreme end of a hypothesised spectrum.

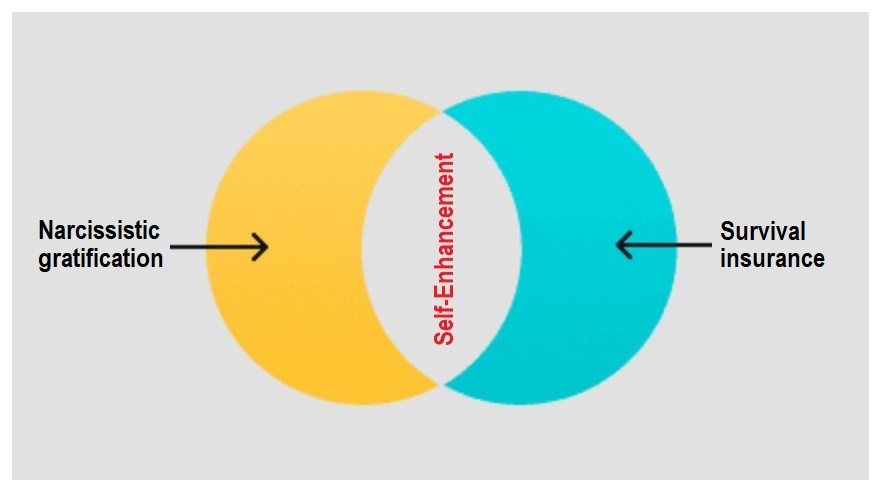

With these points in mind it’s necessary to differentiate between female self-enhancement as an evolutionary survival strategy, versus female self-enhancement as a maladaptive, narcissistic pathology. The narcissistic self-enhancement we see increasingly demonstrated among women today is not a contributor to evolutionary success; on the contrary it works to undermine family ties, corrode intimate relationships, and is also associated with lowering the birth rate – the exact opposites of conditions required for “adaptive.” Lastly, by differentiating hypergamous self-enhancement from narcissistic self-enhancement we avoid the error of encouraging or excusing narcissism under the banner of it being “natural.”

Maladaptive vs. adaptive versions of self-enhancement

REFERENCES:

[1] Grapsas, S., Brummelman, E., Back, M. D., & Denissen, J. J. (2020). The “why” and “how” of narcissism: A process model of narcissistic status pursuit. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(1), 150-172.

[2] Campbell, W. K. (1999). Narcissism and romantic attraction. Journal of Personality and social Psychology, 77(6), 1254.

[3] Wallace, H. M. (2011). Narcissistic self-enhancement. The handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder: Theoretical approaches, empirical findings, and treatments, 309-318.

[4] Campbell, W. K., Brunell, A. B., & Finkel, E. J. (2006). Narcissism, Interpersonal Self-Regulation, and Romantic Relationships: An Agency Model Approach.

[5] Freud, S. (2014). On narcissism: An introduction. Read Books Ltd.

[6] Segal, H., & Bell, D. (2018). The theory of narcissism in the work of Freud and Klein. In Freud’s On Narcissism (pp. 149-174). Routledge.

[7] Holtzman, N. S., & Donnellan, M. B. (2015). The roots of Narcissus: Old and new models of the evolution of narcissism. Evolutionary perspectives on social psychology, 479-489.

[8] Holtzman, N. S. (2018). Did narcissism evolve?. Handbook of Trait Narcissism: Key Advances, Research Methods, and Controversies, 173-181.

[9] Czarna, AZ, Wróbel, M., Folger, LF, Holtzman, NS, Raley, JR, & Foster, JD (2022). Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder: Evolutionary roots and emotional profiles. In TK Shackelford & L. Al-Shawaf (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Evolution and the Emotions. Oxford University Press.

The allure of chivalry

Is benevolent sexism (aka chivalry) attractive to women? According to a new study the answer is, perhaps unsurprisingly, yes.

According to a 2013 study on benevolent sexism by Matthew D. Hammond of the University of Auckland1 a high sense of entitlement disposes women to endorse chivalric customs, such as that women need to be protected, cared for and pampered by males.

Hammond and his colleagues had more than 4,400 men and women complete psychological evaluations to measure their sense of entitlement and adherence to sexist beliefs about women. The beliefs included statements such as, “Women should be cherished and protected by men” and “Women, compared to men, tend to have a superior moral sensibility.”2 This group of individuals was tested again one year later. The researchers found a sense of entitlement in women was associated with stronger endorsement of benevolent sexism. Women who believed they deserved more out of life (and who likely received more out of life) were more likely to endorse benevolent sexist beliefs and their adherence to these beliefs increased over time. The association between a sense of entitlement in men and endorsement of benevolent sexism was weak, by contrast, and did not increase over time.

What these findings provide is evidence that female-benefiting sexism practiced by women is responsible for sexist attitudes toward their own gender, as well as toward men — attitudes which contribute more broadly to the maintenance of gender inequality.

Narcissism relies upon chivalry

In the study narcissistic traits are underlined as the basis of women’s motivation to garner resource-attainments and self-enhancements via the generosity of male chivalry. Some of the core features of narcissism include an inflated sense of self-worth; need for praise, admiration, and social status; an undeserved sense of entitlement; a sense that one deserves nice things; and a belief in one’s superior intelligence and beauty – all without a commensurate level of validity or deservedness. A woman (or man) with such a disposition generally displays efforts to gain esteem, status, and resources by fair means or foul, including by feigning charm, confidence, and an energetic approach to social interactions, and she takes personal responsibility for all successes, while attributing all personal failures to external sources. Narcissistic traits ensure that the individual will act selfishly to secure material gains even when it means exploiting others, and those practicing benevolent sexism tend to encourage such behaviour. According to the authors:

“Benevolent sexism facilitates the capacity to gain material resources and complements feelings of deservingness by promoting a structure of intimate relationships in which men use their access to social power and status to provide for women (Chen et al., 2009). Second, benevolent sexism reinforces beliefs of superiority by expressing praise and reverence of women, emphasizing qualities of purity, morality, and culture which make women the ‘‘fairer sex.’’ Indeed, identifying with these kinds of gender-related beliefs (e.g., women are warm) fosters a more positive self-concept (Rudman, Greenwald, & McGhee, 2001). Moreover, for women higher in psychological entitlement, benevolent sexism legitimizes a self-centric approach to relationships by emphasizing women’s special status within the intimate domain and men’s responsibilities of providing and caring for women. Such care involves everyday chivalrous behaviors, such as paying on a first date and opening doors for women (Sarlet et al., 2012; Viki et al., 2003), to more overarching prescriptions for men’s behavior toward women, such as being ‘‘willing to sacrifice their own well-being’’ to provide for women and to ensure women’s happiness by placing her ‘‘on a pedestal’’ (Ambivalent Sexism Inventory; Glick & Fiske, 1996)… In contrast to the overt benefits that benevolent sexism promises women, men’s endorsement of benevolent sexism reflects making sacrifices for women by relinquishing power in the relationship domain and providing for and protecting their partners (Glick & Fiske, 1996). Moreover, although benevolent sexism portrays men as ‘‘gallant protectors’’ (Glick & Fiske, 2001), it does not emphasize men’s superiority over women or cast men as deserving of praise and provision.” 3

Judging by the above study women’s expectation of chivalric treatment has altered little over the course of the last 800 years since chivalric responsibitities were first instituted. We can take, for example, the voices of two women from history who give voice to the findings of the study; the first written by female author Lucrezia Marinella in 1600:

“Women are honored everywhere with the use of ornaments that greatly surpass men’s, as can be observed. It is a marvelous sight in our city to see the wife of a shoemaker or butcher or even a porter all dressed up with gold chains round her neck, with pearls and valuable rings on her fingers, accompanied by a pair of women on either side to assist her and give her a hand, and then, by contrast, to see her husband cutting up meat all soiled with ox’s blood and down at heel, or loaded up like a beast of burden dressed in rough cloth, as porters are. At first it may seem an astonishing anomaly to see the wife dressed like a lady and the husband so basely that he often appears to be her servant or butler, but if we consider the matter properly, we find it reasonable because it is necessary for a woman, even if she is humble and low, to be ornamented in this way

because of her natural dignity and excellence, and for the man to be less so, like a servant or beast born to serve her.”

Or this from another woman Modesta Pozzo in 1590:

“For don’t we see that men’s rightful task is to go out to work and wear themselves out trying to accumulate wealth, as though they were our factors or stewards, so that we can remain at home like the lady of the house directing their work and enjoying the profit of their labors? That, if you like, is the reason why men are naturally stronger and more robust than us — they need to be, so they can put up with the hard labor they must endure in our service.”

Sources:

[1] Matthew D. Hammond, Chris G. Sibley, and Nickola C. Overall, The Allure of Sexism: Psychological Entitlement Fosters Women’s Endorsement of Benevolent Sexism Over Time

[2] Eric W. Dolan, Self-entitled women are more likely to endorse benevolent sexism, study finds

[3] Matthew D. Hammond, Chris G. Sibley, and Nickola C. Overall [Ibid]

[4] Ruth Styles, The fickle face of feminism: Women are fine with sexism… as long as it benefits them

[5] Lucrezia Marinella: gynocentrism in 1600

[6] Modesta Pozzo: gynocentrism in 1590