Querelle des Femmes

Timeline of gynocentric culture

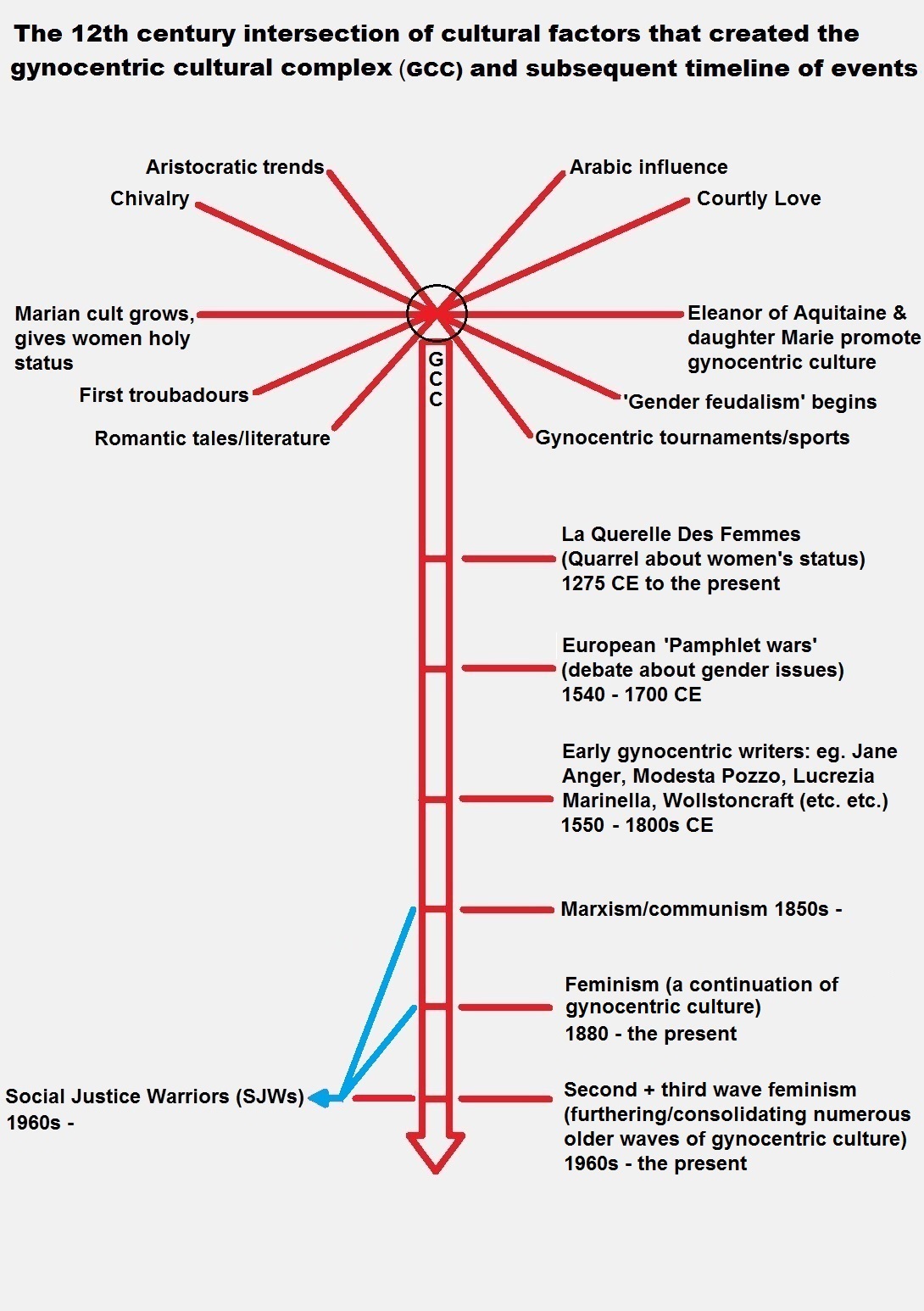

The following timeline details the birth of gynocentric culture along with significant historical events that ensured its survival. Prior to 1200 AD broadspread gynocentric culture simply did not exist, despite evidence of isolated gynocentric acts and events. It was only in the Middle Ages that gynocentrism developed cultural complexity and became a ubiquitous and enduring cultural norm.

1102 AD: Gynocentrism trope first introduced

William IX, Duke of Aquitaine, the most powerful feudal lord in France, wrote the first troubadour poems and is widely considered the first troubadour. Parting with the tradition of fighting wars strictly on behalf of man, king, God and country, William is said to have had the image of his mistress painted on his shield, whom he called midons (my Lord) saying that, “It was his will to bear her in battle, as she had borne him in bed.”1

1152 AD: Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine enlists the poet Bernard de Ventadorn to compose songs of love for her and her husband, Henry II. The songs lay down a code of chivalric behaviour for how a good man should treat a “lady,” which Eleanor employs in an apparent attempt to civilize her husband and his male associates. Eleanor and other noblewomen utilize poetry and song for setting expectations of how men should act around them, thus was born the attitude of romantic chivalry promoting the idea that men need to devote themselves to serving the honour, purity and dignity of women.2

1168 – 1198 AD: Gynocentrism trope elaborated, given imperial patronage

The gynocentrism trope is further popularized and given imperial patronage by Eleanor and her daughter Marie.3 At Eleanor’s court in Poitiers Eleanor and Marie completed the work of embroidering the Christian military code of chivalry with a code for romantic lovers,4 thus putting women at the center of courtly life, and placing romantic love on the throne of God himself – and in doing so they had changed the face of chivalry forever. Key events are:

–1170 AD: Eleanor and Marie established the formal Courts of Love presided over by themselves and a jury of 60 noble ladies who would investigate and hand down judgements on love-disputes according to the newly introduced code governing gender relations. The courts were modelled precisely along the lines of the traditional feudal courts where disputes between retainers had been settled by the powerful lord. In this case however the disputes were between lovers.

-1180 AD: Marie directs Chrétien de Troyes to write Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart, a love story about Lancelot and Guinevere elaborating the nature of gynocentric chivalry. Chrétien de Troyes abandoned this project before it was completed because he objected to the implicit approval of the adulterous affair between Lancelot and Guinevere that Marie had directed him to write.6 But the approval of the legend was irresistible – later poets completed the story on Chrétien’s behalf. Chrétien also wrote other famous romances including Erec and Enide.

-1188 AD: Marie directs her chaplain Andreas Capellanus to write The Art of Courtly Love. This guide to the chivalric codes of romantic love is a document that could pass as contemporary in almost every respect, excepting for the outdated class structures and assumptions. Many of the admonitions in Andreas “textbook” clearly come from the women who directed the writing.4

1180 – 1380 AD: Gynocentric culture spreads throughout Europe

In two hundred years gynocentric culture spread from France to become instituted in all the principle courts of Europe, and from there went on to capture the imagination of men, women and children of all social classes. According to Jennifer Wollock,5 the continuing popularity of chivalric love stories is also confirmed by the contents of women’s libraries of the late Middle Ages, literature which had a substantial female readership including mothers reading to their daughters. Aside from the growing access to literature, gynocentric culture values spread via everyday interactions among people in which they created, shared, and/or exchanged the information and ideas.

1386 AD: Gynocentric concept of ‘gentleman’ formed

Coined in the 1200’s, the word “Gentil man” soon became synonymous with chivalry. According to the Oxford Dictionary gentleman came to refer by 1386 to “a man with chivalrous instincts and fine feelings”. Gentleman therefore implies chivalric behaviour and serves as a synonym for it; a meaning that has been retained to the present day.

1400 AD: Beginning of the the Querelle des Femmes

The Querelle des Femmes or “quarrel about women” technically had its beginning in 1230 AD with the publication of Romance of the Rose. However it was Italian-French author Christine de Pizan who in 1400 AD turned the prevailing discussion about women into a debate that continues to reverberate in feminist ideology today. The basic theme of the centuries-long quarrel revolved, and continues to revolve, around advocacy for the rights, power and status of women.

21st century: Gynocentrism continues

The now 1000 year long culture of gynocentrism continues with the help of traditionalists eager to preserve gynocentric customs, manners, taboos, expectations, and institutions with which they have become so familiar; and also by feminists who continue to find new and often novel ways to increase women’s power with the aid of chivalry. The modern feminist movement has rejected some chivalric customs such as opening car doors or giving up a seat on a bus for women; however they continue to rely on ‘the spirit of chivalry’ to attain new privileges for women: opening car doors has become opening doors into university or employment via affirmative action; and giving up seats on busses has become giving up seats in boardrooms and political parties via quotas. Despite the varied goals, contemporary gynocentrism remains a project for maintaining and increasing women’s power with the assistance of chivalry.

Sources:

[1] Maurice Keen, Chivalry, Yale University Press, 1984. [Note: 1102 AD is the date ascribed to the writing of William’s first poems].

[2] The History of Ideas: Manners

[3] The dates 1168 – 1198 cover the period beginning with Eleanor and Marie’s time at Poitiers to the time of Marie’s death in 1198.

[4] C. J. McKnight, Chivalry: The Path of Love, Harper Collins, 1994.

[5] Jennifer G. Wollock, Rethinking Chivalry and Courtly Love, Praeger, 2011.

[6] Uitti, Karl D. (1995). Chrétien de Troyes Revisited. New York, New York: Twayne Publishers.

La Querelle des Femmes

The 800 year old Querelle des Femmes translates as the “quarrel about women” and amounts to what we today refer to as the gender-war. In its narrow sense, this term refers to a genre of Latin and French writing in which the superiority of one or the other sex has been proposed with the primary aim of determining the status of women.

The timeframe of the querelle begins in the twelfth century, and after 800 years of debate finds itself perpetuated in the feminist-driven reiterations of today (though some authors claim, unconvincingly, that the larger querelle came to an end in the 1700s).

For more about the history of La Querelle des Femmes, the following paper by historian Joan Kelly is instructive. The paper was written with a feminist focus thus leaving out all but the most superficial characterization of the male experience of gender relations. Nevertheless it provides much important history and for that I have no hesitation in recommending it.

* * *

Early Feminist Theory and the Querelle des Femmes

By Joan Kelly (1982)

We generally think of feminism, and certainly of feminist theory, as taking rise in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Most histories of the Anglo-American women’s movement acknowledge feminist “forerunners” in individual figures such as Anne Hutchinson, and in women inspired by the English and French revolutions, but only with the women’s rights conference at Seneca Falls in 1848 do they recognize the beginnings of a continuously developing body of feminist thought.

Histories of French feminism claim a longer past. They tend to identify Christine de Pisan (1364-1430?) as the first to hold modern feminist views and then to survey other early figures who followed her in expressing pro-woman ideas up until the time of the French Revolution. New work is now appearing that will give us a fuller sense of the richness, coherence, and continuity of early feminist thought, and I hope this paper contributes to that end.

What I hope to demonstrate is that there was a 400-year-old tradition of women thinking about women and sexual politics in European society before the French Revolution. Feminist theorizing arose in the fifteenth century, in intimate association with and in reaction to the new secular culture of the modern European state. It emerged as the voice of literate women who felt themselves and all women maligned and newly oppressed by that culture, but who were empowered by it at the same time to speak out in their defense. Christine de Pisan was the first such feminist thinker, and the four-century-long debate that she sparked, known as the querelle des femmes, became the vehicle through which most early feminist thinking evolved.

The early feminists did not use the term “feminist,” of course. If they had applied any name to themselves, it would have been something like defenders or advocates of women, but it is fair to call this long line of prowomen writers that runs from Christine de Pisan to Mary Wollstonecraft by the name we use for their nineteenth- and twentieth-century descendants. Latter-day feminism, for all its additional richness, still incorporates the basic positions the feminists of the querelle were the first to take.

![]() To read the rest of Joan Kelly’s essay online click here

To read the rest of Joan Kelly’s essay online click here

See also related: Querelle du Mariage

About gynocentrism

|

Gynocentrism (n.) refers to a dominant focus on women’s needs and wants relative to men’s needs and wants. This can happen in the context of cultural conventions, social institutions, political policies, and in gendered relationships.1 |

Introduction

Cultural gynocentrism emerged in Medieval Europe during a time of profound cross-cultural exchange and shifting gender customs. From the 11th century onward, European society absorbed influences ranging from Arabic love poetry to aristocratic courtship trends, alongside the rise of the Marian cult. This climate was further shaped by figures such as Eleanor of Aquitaine and her daughter Marie who transformed the ideal of chivalry into a code of male service to women —a tradition now known as courtly love.

Courtly love was popularized through the work of troubadours, minstrels, playwrights, and by commissioned romance writers whose stories laid down a model of romantic fiction that remains the most commercially successful genre of literature to this day. That confluence of factors generated the conventions that continue to drive gynocentric practices to the present.

Gynocentrism as a cultural phenomenon

The primary elements of gynocentric culture, as we experience it today, are derived from practices originating in medieval society such as feudalism, chivalry and courtly love. These traditions continue to shape contemporary society in subtle but enduring ways. In this context, various scholars and writers have described gynocentric patterns as a form of “sexual feudalism.”

For example, in 1600, the Italian writer Lucrezia Marinella observed that women of lower social classes were often treated as superiors, while men served them like knightly retainers and beasts of burden. Similarly, Modesta Pozzo, writing in 1590, remarked:

“Don’t we see that men’s rightful task is to go out to work and wear themselves out trying to accumulate wealth, as though they were our factors or stewards, so that we can remain at home like the lady of the house directing their work and enjoying the profit of their labors? That, if you like, is the reason why men are naturally stronger and more robust than us — they need to be, so they can put up with the hard labor they must endure in our service.”2

The golden casket at the head of this page depicting scenes of servile behaviour toward women were typical of courtly love culture of the Middle Ages. Such objects were given to women as gifts by men seeking to impress. Note the woman standing with hands on hips in a position of authority, and the man being led around by a neck halter, his hands clasped in a position of subservience.

It’s clear that much of what we today call gynocentrism was invented in this early period, where the feudal template was employed as the basis for a new model for love in which men would play the role of a vassal to women who assumed the role of an idealized Lord.

C.S. Lewis, in the middle of the 20th Century, referred to this historical revolution as “the feudalisation of love,” and stated that it has left no corner of our ethics, our imagination, or our daily life untouched. “Compared with this revolution,” states Lewis, “the Renaissance is a mere ripple on the surface of literature.”3 Lewis further states;

“Everyone has heard of courtly love, and everyone knows it appeared quite suddenly at the end of the eleventh century at Languedoc. The sentiment, of course, is love, but love of a highly specialized sort, whose characteristics may be enumerated as Humility, Courtesy, Adultery and the Religion of Love. The lover is always abject. Obedience to his lady’s lightest wish, however whimsical, and silent acquiescence in her rebukes, however unjust, are the only virtues he dares to claim. Here is a service of love closely modelled on the service which a feudal vassal owes to his lord. The lover is the lady’s ‘man’. He addresses her as midons, which etymologically represents not ‘my lady’ but ‘my lord’. The whole attitude has been rightly described as ‘a feudalisation of love’. This solemn amatory ritual is felt to be part and parcel of the courtly life.” 4

With the advent of (initially courtly) women being elevated to the position of ‘Lord’ in intimate relationships, and with this general sentiment diffusing to the masses and across much of the world today, we are justified in talking of a gynocentric cultural complex that affects, among other things, relationships between men and women. Further, unless evidence of widespread gynocentric culture can be found prior to the Middle Ages, then gynocentrism is approximately 1000 years old. In order to determine if this thesis is valid we need to look further at what we mean by “gynocentrism”.

The term gynocentrism has been in circulation since the 1800’s, with the general definition being “focused on women; concerned with only women.”5 From this definition we see that gynocentrism could refer to any female-centered practice, or to a single gynocentric act carried out by one individual. There is nothing inherently wrong with a gynocentric act (eg. celebrating Mother’s Day) , or for that matter an androcentric act (celebrating Father’s Day). However when a given act becomes instituted in the culture to the exclusion of other acts we are then dealing with a hegemonic custom — i.e. such is the relationship custom of elevating women to the position of men’s social, moral or spiritual superiors.

Author of Gynocentrism Theory Adam Kostakis has attempted to expand the definition of gynocentrism to refer to “male sacrifice for the benefit of women” and “the deference of men to women,” and he concludes; “Gynocentrism, whether it went by the name honor, nobility, chivalry, or feminism, its essence has gone unchanged. It remains a peculiarly male duty to help the women onto the lifeboats, while the men themselves face a certain and icy death.”6

While we can agree with Kostakis’ descriptions of assumed male duty, the phrase gynocentric culture more accurately carries his intention than gynocentrism alone. Thus when used alone in the context of this website gynocentrism refers to part or all of gynocentric culture, which is defined here as any culture instituting rules for gender relationships that benefit females at the expense of males across a broad range of measures.

At the base of gynocentric culture lies the practice of enforced male sacrifice for the benefit of women. If we accept this definition we must look back and ask whether male sacrifices throughout history were always made for the sake women, or alternatively for the sake of some other primary goal? For instance, when men went to die in vast numbers in wars, was it for women, or was it rather for Man, King, God and Country? If the latter we cannot then claim that this was a result of some intentional gynocentric culture, at least not in the way I have defined it here. If the sacrifice isn’t intended directly for the benefit women, even if women were occasional beneficiaries of male sacrifice, then we are not dealing with gynocentric culture.

Male utility and disposability strictly “for the benefit of women” comes in strongly only after the advent of the 12th century gender revolution in Europe – a revolution that delivered us terms like gallantry, chivalry, chivalric love, courtesy, damsels, romance and so on. From that period onward gynocentric practices grew exponentially, culminating in the demands of today’s feminist movement. In sum, gynocentrism (ie. gynocentric culture) was a patchy phenomenon at best before the middle ages, after which it became ubiquitous.

With this in mind it makes little sense to talk of gynocentric culture starting with the industrial revolution a mere 200 years ago (or 100 or even 30 yrs ago), or of it being two million years old as some would argue. We are not only fighting two million years of genetic programming; our culturally constructed problem of gender inequity is much simpler to pinpoint and to potentially reverse. All we need do is look at the circumstances under which gynocentric culture first began to flourish and attempt to reverse those circumstances. Specifically, that means rejecting the illusions of romantic love (feudalised love), along with the practices of misandry, male shaming and servitude that ultimately support it.

La Querelle des Femmes, and advocacy for women

The Querelle des Femmes translates as the “quarrel about women” and amounts to what we might today call a gender-war. The querelle had its beginning in twelfth century Europe and finds its culmination in the feminist-driven ideology of today (though some authors claim, unconvincingly, that the querelle came to an end in the 1700s).

The basic theme of the centuries-long quarrel revolved, and continues to revolve, around advocacy for the rights, power and status of women, and thus Querelle des Femmes serves as the originating title for gynocentric discourse.

To place the above events into a coherent timeline, chivalric servitude toward women was elaborated and given patronage first under the reign of Eleanor of Aquitaine (1137-1152) and instituted culturally throughout Europe over the subsequent 200 year period. After becoming thus entrenched on European soil there arose the Querelle des Femmes which refers to the advocacy culture that arose for protecting, perpetuating and increasing female power in relation to men that continues, in an unbroken tradition, in the efforts of contemporary feminism.7

Writings from the Middle Ages forward are full of testaments about men attempting to adapt to the feudalisation of love and the serving of women, along with the emotional agony, shame and sometimes physical violence they suffered in the process. Gynocentric chivalry and the associated querelle have not received much elaboration in men’s studies courses to-date, but with the emergence of new manuscripts and quality English translations it may be profitable to begin blazing this trail.8

References

1. Wright, P., What’s in a suffix? taking a closer look at the word gyno–centrism

2. Modesta Pozzo, The Worth of Women: their Nobility and Superiority to Men

3. C.S. Lewis, Friendship, chapter in The Four Loves, HarperCollins, 1960

4. C.S. Lewis, The Allegory of Love, Oxford University Press, 1936

5. Dictionary.com – Gynocentric

6. Adam Kostakis, Gynocentrism Theory – (Published online, 2011). Although Kostakis assumes gynocentrism has been around throughout recorded history, he singles out the Middle Ages for comment: “There is an enormous amount of continuity between the chivalric class code which arose in the Middle Ages and modern feminism… One could say that they are the same entity, which now exists in a more mature form – certainly, we are not dealing with two separate creatures.”

7. Joan Kelly, Early Feminist Theory and the Querelle des Femmes (1982), reprinted in Women, History and Theory, UCP (1984)

8. The New Male Studies Journal has published thoughtful articles touching on the history and influence of chivalry in the lives of males.