The following description of chivalry is from an article ‘The Condition of Women During the Ages of Chivalry’ from the book The Ladies’ Museum, Volume 29 published in 1829.

To read the rest of this article click here.

The following description of chivalry is from an article ‘The Condition of Women During the Ages of Chivalry’ from the book The Ladies’ Museum, Volume 29 published in 1829.

To read the rest of this article click here.

The following account on the influence of women on manners and literature in Europe is taken from a review in The Analectic Magazine – vol XII published in Philadelphia in the year 1818.

To read the rest of this 25 page article click here and begin on page 311.

Lucrezia Marinella (c.1571-1653) was a Venetian author and early advocate of gynocentric feminism. She describes gender relations in Europe as based on males acting as “servants,” “subjects,” “beasts of burden,” or “butlers” toward women who are universally viewed as men’s superiors.

The following excerpts are from her book The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men:

THE REASONS FOR MEN’S NOBLE TREATMENT OF WOMEN AND THE THINGS THEY SAY ABOUT WOMEN

“Even though men upbraid and defame the female sex each day in garrulous and biting language, and search in every possible way to obscure the noble actions of women, they are forced in spite of themselves, by consciences that are governed by truth, to honor worthy women and praise them to the skies. They do this in words and in writings that demonstrate women’s superiority beyond any doubt. We see constantly and in every place and occasion that women are honored by men. That is why men bow to them and make way for them when walking, why they raise their hats to them and wait on them at the table like servants, accompany them bareheaded in the streets, and give up their seats to them. These obvious signs of honor are performed toward women not merely by low, plebeian men but also by dukes and kings, who raise their hats whether greeting princesses or ladies of mediocre condition.

It may be superfluous, but I will give two examples of these princes. The first is the King of France, who honors every lady with bows and salutations; the second the King of Spain, who, though extremely powerful, raises his cap or hat on meeting a noblewoman, which is something he would not do to any male subject, even if he were a prince. Uncovering the head, standing up, and giving way are undoubtedly signs and proofs of honor, and since they are signs of honor, women must be nobler than the men who honor them, because the object of such honor is always more nobler than the person who honors them.

Nobody honors another person unless they know that the person has some gift or quality that is superior to his own… It is necessary therefore to conclude that women are nobler than men because they are honored by men. Further indications of honor are the ornaments bestowed on women, who are permitted to dress themselves in purple and cloth of gold with diverse embroideries decorated with pearls and diamonds, and to adorn their heads with pretty gold ornaments and finest enamel and precious stones. These things are forbidden to men, apart from rulers. If any other man dared to dress himself in cloth of gold or such like, he would be mocked and pointed out as light-minded or a downright buffoon.

“In Germany, where men are not permitted any sort of festive attire unless they are noble, every little woman adorns herself with festive drapes and different types of necklace, as is the habit all over the world. Women are honored everywhere with the use of ornaments that greatly surpass men’s, as can be observed. It is a marvelous sight in our city to see the wife of a shoemaker or butcher or even a porter all dressed up with gold chains round her neck, with pearls and valuable rings on her fingers, accompanied by a pair of women on either side to assist her and give her a hand, and then, by contrast, to see her husband cutting up meat all soiled with ox’s blood and down at heel, or loaded up like a beast of burden dressed in rough cloth, as porters are.

At first it may seem an astonishing anomaly to see the wife dressed like a lady and the husband so basely that he often appears to be her servant or butler, but if we consider the matter properly, we find it reasonable because it is necessary for a woman, even if she is humble and low, to be ornamented in this way because of her natural dignity and excellence, and for the man to be less so, like a servant or beast born to serve her.

As well as in the ways already narrated, women have been honored by men with great and eminent titles that are used by them continually, being commonly referred to as donne, for, as was demonstrated in the first chapter, the name donna means lady and mistress. When men refer to women thus, they honor them, though they may not intend to, by calling them ladies, even if they are humble and of a lowly disposition. In truth, to express the nobility of this sex men could not find a more appropriate and fitting name than donna, which immediately shows women’s superiority and precedence over men, because by calling women mistress they show themselves of necessity to be subjects and servants.

“Women’s nobility and excellence is recognized by the French and Spanish more than by the Italians. In these countries they are allowed to inherit estates, succeeding not only to dukedoms but to principalities exactly as men do. Not only to principalities, but to the monarchy itself, like the sister of the King of Spain, who was able to ascend to the monarchy, as well as have dominion over numerous other principalities.

Women who inherit estates can be seen every day in France and England. The Germans too recognize women’s superiority. The women there conduct all the business dealings and mercantile transactions in the cities while the men remain at the stoves. This also occurs in Flanders and in France. In France men may not spend even a centime unless at the request of their wives, and women not only administrate business dealings and sales but private income as well. What do you think? Are not women, as I have proved, known by men to be nobler than them, seeing that they confess it with their own mouths? What more is there for me to say?”

_____________________________

The following video series by Barbarossaaa discuss what he calls “traditionalism,” a shorthand term for traditional gynocentric culture and its practices.

Schlafly podcast gives ridiculous divorce advice:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y7E9Hgn2MLY&w=560&h=315]

Traditionalism and feminism, the great gynocentrisms of our time:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ah2rh-fKifQ&w=560&h=315]

Organic dissolution of traditionalism, and small government platitudes:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nt8LtMl0TI0&w=560&h=315]

Traditionalism and chivalry = the other feminism:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D_b8Gs6WoW0&w=560&h=315]

Traditional Relationships…nothing but business and a bottom line:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2-myk23yTyM&w=420&h=315]

Do men Justify their own exploitation?

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T9zCoDCVyxA&w=420&h=315]

To learn more about MGTOW see YouTube for some excellent channels and discussions: Men Going Their Own Way

The following video from ManWomanMyth’s YouTube Channel provide a sample of cultural practices that characterise the gynocentrism of today’s world.

Modern dictionaries usually define gynarchy as a political system governed by women or a woman. For a more nuanced understanding it’s important to recognise that “the political system” that women govern may actually be staffed by male servants called prime ministers, presidents, or politicians who work on behalf of the ruling female gender.[1] In her book What’s Right With Feminism, Cassandra Langer gives a concise definition that accounts for the proxy role of male leaders: “Gynarchy refers to government by women, or women-centered government.” – PW

The following articles show that Columbia was more than an empty symbol of America’s pedestalisation of women (*click articles to enlarge):

The Philadelphia Record – 1903

England and the English from an American Point of View – 1909

From Dublin to Chicago: Some Notes on a Tour in America – 1914

Albert Einstein declares Women Rule Here – 1921

By Diana Davison

A long time ago (15th century) in a land not too far away (France) a protofeminist named Christine de Pizan initiated a public debate later named La Querelle de la Rose. Simone de Beauvoir honours Pizan as the first woman to “take up her pen in defence of her sex”[1] but Christine was not fighting for new rights, she was strictly defending the chivalry-based gynocentric culture that she saw crumbling away before her eyes.

Though some feminists deny Christine’s status as a member of the gang, she did seem to have set the standard for how women change the public narrative; lies, elitism, deception and manipulation of history bordering on fraud.

Like all feminists who followed in her footprints, she set a Machiavellian example. The end justifies the means and, while you re-write “herstory”, make sure to claim you are meek and helpless the whole time.

But let us go back to the start of this adventure. We shall travel to c1275 when a man of some talent took up an incomplete poem called La Roman de La Rose and added a whopping 18,824 additional lines to the original 4,000 to create what would become one of the most widely read works of medieval times. Not only did the second author, Jean de Meun, create a cult following, his work was mimicked by Chaucer and Dante. Overall, a charmingly good chap for literary culture.

For over a hundred years this poem proliferated, was translated, adored, and revered as a work of genius. It outlined the troubles and challenges a youth may face when trying to woo a young lady in the world of chivalry. As in most good stories, the goal was not attained easily.

Presented in a dreamlike setting, our hero is guided by personified attributes such as Reason and Genius who help him to bypass all the lady’s defences and capture her “castle.” The language is considered quite risque for the times.

Around 1401 a gentleman named Jean de Montreuil, who served as secretary in the king’s chancery of France, was convinced to read the poem and wrote a glowing review which circulated about the land. It crossed the path of a woman named Christine de Pizan.

Christine was in a unique position compared to other women of her time. She had been raised in the court where her father, despite her mother’s disapproval, urged her to learn how to read and write. These skills came in handy after both her father and husband died quite young leaving Christine with debt and children. She was not overly pleased with her reduction of social status but managed to secure some work as a copyist instead of having to work at spinning or other demeaning trades.

She had begun by writing romantic poetry and secured some patrons who paid her for the work she sent them. She was a clever mimic and was able to write in whatever style her patrons preferred. She would likely have continued to meet survival needs as things were but decided, upon seeing Montreuil’s treatise, to take a chance and use her pen in defence of her desire to improve her career.

She had begun by writing romantic poetry and secured some patrons who paid her for the work she sent them. She was a clever mimic and was able to write in whatever style her patrons preferred. She would likely have continued to meet survival needs as things were but decided, upon seeing Montreuil’s treatise, to take a chance and use her pen in defence of her desire to improve her career.

Thus began an exchange of letters between Christine and defenders of the poem La Roman de La Rose.

These letters became public because Christine de Pizan decided to publish them. She was quite creative in her publishing by arranging them out of chronological order and removing the best arguments that her opponents had offered. Just like a feminist.

Some of the missing letters have since been recovered.

Christine’s main problem with the famous poem amounts to censorship. She takes exception to the naming of genitals and with advice being given as to how to trick women into having sex. Christine was a very conservative Christian. As such, you might think that she really did find the whole storyline repulsive if she hadn’t stated in a letter that the debate was “good-humored, an example of a difference of opinion between worthy persons”[2] and mentioned in another letter that a reply made her laugh.

The Romance of the Rose is rather bawdy and, at times, obscene: kind of like The Vagina Monologues.

Christine intitiated the debate by replying to a letter she acknowledged was not addressed to her. She bypassed that fact by publishing the letters out of order to make her “reply” look solicited.

She begins by stating that her opponents are very learned and that she is very ignorant, which she hopes will not taint their reading of her correspondence. She claims to be weak and timid. Of course, only timid people publish private letters and send copies of it to the Queen.

She begins by stating that her opponents are very learned and that she is very ignorant, which she hopes will not taint their reading of her correspondence. She claims to be weak and timid. Of course, only timid people publish private letters and send copies of it to the Queen.

Speaking of the Queen, who was one of Christine’s patrons, one of Pizan’s approaches was to link female virtue directly to Queen Isabeau of Bavaria “to the point at which the Queen becomes synonymous with virtue, Christine essentially lays the Queen under an obligation to accept her position; not to do so would be to reject her very self.”[3]

Nice trick.

Despite feminist claims that Christine tackled this monumental task alone, she was abetted by Jean Gerson, a long time family friend from her courtly days. Gerson was a strange bedfellow but he and Christine shared some religious ideals and were united both on the misogyny front and in speaking out about the “body politic” in other works. He’s not always mentioned in the discussions of the Querelle because feminists would like you to think Christine didn’t have a white knight helping her out.

The problem faced by both Pizan and Gerson was that de Meun’s poem was, and is, a work of art. When his characters speak they speak as that character would and do not represent the thinking of either the author or God. That is often the problem of censorship fanatics. The other big problem is that they have to admit they actually read the cursed thing.

When you read something distasteful, it is hard to blame anyone but yourself for the fact that you read it. If you didn’t read it or look at it, you can hardly have an opinion. Christine claims to have skim read over the worst of the worst but still approaches it as if she can fully assess the artistic merits of the work.

The accusations against her, which she deletes from her version of events, are that she is a novice who can’t comprehend advanced works and that she is speaking out of turn because she got a lot of recent praise and is suddenly full of her own ego:

“Yet what do we make of Pierre Col’s contention, suppressed by Christine, that her actions have resulted from her envy of ‘la tres elevee haultesse du liver’ [the very loftiness of the book], and that she had better be careful so as not to suffer the fate of the crow who, when ‘someone praised his song, began to sing louder than usual and let his mouthful fall.'”[4]

Christine responds with continued claims to humility and simplicity which, ironically and with calculation, guarantee her fame.

While feminists praise Pizan as a defender of women, only a third of what she wrote in the debate is devoted to perceptions of women. The majority of her complaint is pure Christian objection to obscenity.[5] The purpose of her diatribe can be discerned in the writings that followed, after winning the prestige to write full fledged books.

So what did she write next?

The iconic work in the list of some feminist “must read” resources is Christine de Pizan’s City of Ladies. This is the first book that she published after the Querelle which took up the cause of women.

The City of Ladies copies the format of previous male writers, like de Muen, who present a story in allegorical dream sequence. As a character in her own book Pizan is ordered by her ficitonal ladies of Reason, Rectitude, and Justice, to construct an city with her pen in which women can take shelter. Not all women, only “virtuous” women of her discernment. Christine doesn’t actually believe that all women are good and pure and worthy of men’s love, she just wants to build really solid walls behind which some women can hide so that they can continue to be treated as godly creatures while the other women burn in fucking hell. It was a form of alchemy: Burn off the undesirables.

“Only ladies who are of good reputation and worthy of praise will be admitted into this city. To those lacking in virtue, its gates will remain forever closed” [6]

Those whores are giving women a bad name. Slut-shaming Central.

The gates of Pizan’s City are locked tight to adulteresses, lustful women of any sort, and those who don’t uphold Christine’s religious ideals. She has built this city on the foundations of mythical women, appointed the Virgin Mary as queen (who she alludes to herself as representing), and predicts that her city of imaginary wonder will never fall. It can’t because it’s not real.

The gates of Pizan’s City are locked tight to adulteresses, lustful women of any sort, and those who don’t uphold Christine’s religious ideals. She has built this city on the foundations of mythical women, appointed the Virgin Mary as queen (who she alludes to herself as representing), and predicts that her city of imaginary wonder will never fall. It can’t because it’s not real.

If we had any doubt about Christine’s intentional trickery, we need look no further than the pages of this debut novel which, unlike the letters of the Querelle, are unmolested. She takes examples of awesome women from the Bible and pagan mythologies and leaves out all the bad parts of the stories so that they all look virtuous.

For example, Abraham’s wife, Sarah, becomes a woman who was so lusted after that King Pharaoh forcibly stole her from her husband. For those who actually read the bible, you’ll find out that Sarah and Abraham tricked Pharaoh by telling him they were siblings so that he might fall in love and give her many riches. When God punished Pharaoh for seducing a married woman Pharaoh was flabbergasted and gave them whatever they wanted just to get the fuck out of town. They pulled this trick twice. And it turns out they actually were brother and sister. God didn’t seem to care about that.

Christine laments that one of her heroines, Semaramis, married her son to avoid having to share her kingdom with another woman but excuses her because it wasn’t a law at the time that she shouldn’t do that. That Semaramis managed to defend her kingdom after the death of her husband was more important than the laws of nature. The laws of nature are somewhat mutable in Christine’s world, when it suits her purpose.

“As for those men who are slanderous by nature, it’s not surprising if they criticize women, given that they attack everyone indiscriminately. You can take it from me that any man who wilfully slanders the female sex does so because he has an evil mind, since he’s going against both reason and nature.” [7]

So it’s in man’s nature to go against nature? It’s not hard to argue against logic like that.

In the final reading, we are left to wonder what it is Christine was really trying to accomplish. Did she think women were strong, capable people or objects to be fawned over and worshipped like children or gods? Christine answers that upon seeing the perfect dream ladies of her vision who arrive to show her the path of truth:

“I didn’t know which of my senses was the more struck by what she said: whether it was my ears as I took in her stirring words, or my eyes as I admired her great beauty and dress, her noble bearing and face.” [8]

Christine! You misogynist!!

How dare you objectify these women with your gaze?

Christine’s “city” presents and shelters women as goddesses. Like Pygmalion, who was uninterested in real women, she sculpts the perfect female so that men can worship the illusion. Christine was a traditionalist attempting to uphold and entrench all the privileges enjoyed by her gender since chivalric love had been introduced.

As a pioneer of feminism, she taught those who followed that every female flaw which can’t be excused can be erased from herstory.

Sources:

1. Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, p105

2. Heather Bamford, Remember the giver(s): the creation of the Querelle and notions of sender and recipient in University of California, Berkeley, MS 109, 2009

3. ibid

4. David F. Hult, Words and Deeds: Jean de Meun’s “Romance of the Rose” and the Hermeneutics of Censorship, New Literary History, Vo. 28, No. 2, Medieval Studies (Spring, 1997)

5. Ibid

6. Christine de Pizan, City of Ladies, p11

7. ibid, p19-20

8. ibid, p9

Editor’s note: feature image by Hans Splinter. –PW

The Art of Courtly Love was written by Andreas Capellanus in 1190. The volume falls into three large units or “books.” Book One, “Introduction to the Treatise on Love,” defines love as “a certain inborn suffering derived from the sight of and excessive meditation upon the beauty of the opposite sex, which causes each one to wish above all things the embraces of the other.” There is no question that love is suffering, says Andreas, because “before the love becomes equally balanced on both sides there is no torment greater, since the lover is always in fear that his love may not gain its desire.”

True love is an ennobling experience, for it can endow a man with nobility of character, can cause a proud man to be humble, and can cause a selfish man to perform many graceful services:

O what a wonderful thing is love, which makes a man shine with so many virtues and teaches everyone, no matter who he is, so many good traits of character! . . . It adorns a man, so to speak, with the virtue of chastity, because he who shines with the light of one love can hardly think of embracing another woman, even a beautiful one. For when he thinks deeply of his beloved the sight of any other woman seems to his mind rough and rude.

Much of Book One is a series of dialogues showing how a man of one class might speak of his love with a woman of his own or another class. Here are excerpts from the “seventh dialogue,” one in which a man of the higher nobility speaks with a woman of the simple nobility. He has not before met the woman, but he has heard her praised by others:

THE MAN SAYS: I ought to give God greater thanks than any other living man in the whole world because it is now granted me to see with my eyes what my soul has desired above all else to see. . . . And I now know in very truth that a human tongue is not able to tell the tale of your beauty and your prudence. . . . And I wish ever to dedicate to your praise all the good deeds that I do and to serve your reputation in every way. For whatever good I may do, you may know that it is done with you in mind. . . .

THE WOMAN SAYS: I am bound to give you many thanks for lauding me with such commendations and exalting me with such high praise . . . I am therefore glad if I am to you a cause and origin of good deeds, and so far as I am able I shall always and in all things give you my approval when you do well. . . .

THE MAN SAYS: I have chosen you from among all women to be my mighty lady, to whose services I wish ever to devote myself and to whose credit I wish to set down all my good deeds. From the bottom of my heart I ask you mercy, that you may look upon me as your particular man, just as I have devoted myself particularly to serve you, and that my deeds may obtain from you the reward I desire. . . .

THE WOMAN SAYS: Your request that I should consider you as my particular man, just as you are particularly devoted to my service, and that I should give you the reward you hope for, I do not see how I can grant, since such partiality might be to the disadvantage of others who have as much desire to serve me as you have, or perhaps even more. Besides I am not perfectly clear as to what the reward is that you expect from me; you must explain yourself more clearly. . . .

THE MAN SAYS: The reward I ask you to promise to give me is one which it is unbearable agony to be without, while to have it is to abound in all riches. It is that you should be pleasant to me unless your desire is opposed to me. It is your love which I seek, in order to restore my health.. . .

THE WOMAN SAYS: You seem to be wandering a long way from the straight path of love and to be violating the best custom of lovers, because you are in such haste to ask for love. For the wise and well-taught lover, when conversing for the first time with a lady whom he has not previously known, should not ask in specific words for the gifts of love. We are separated by too wide and too rough an expanse of country to be able to offer each other love’s solaces or to find proper opportunities for meeting. Lovers who live near together can cure each other of the torments that come from love. . . . Therefore everybody should try to find a lover who lives near by.

The woman argues that love really can exist between husband and wife. Neither she nor he will yield on this crucial point, and in the end they submit the matter to the Countess of Champagne and agree to abide by her ruling on this question. She replies to the woman’s letter in one dated May 1, 1174: “We declare and we hold as firmly established that love cannot exert its powers between two people who are married to each other. For lovers give each other everything freely, under no compulsion of necessity, but married people are in duty bound to give in to each other’s desires and deny themselves to each other in nothing.”

Here are excerpts from the “eighth dialogue,” one in which a man and woman both of the higher nobility enter into a dialogue. Andreas states that if a man of higher nobility should seek the love of a woman of the same class, he should first above all things follow the rule to use soft and gentle words, and he should take care not to say anything that would seem to deserve reproof. For a noblewoman or a woman of higher nobility is found to be very ready and bold in censuring the deeds or the words of a man of the higher nobility, and she is very glad if she has a good opportunity to say something to ridicule him.

THE MAN SAYS: Indeed it is true that god has inclined all good men in this life to serve your desires and those of other ladies, and it seems to me that this is for the very clear reason that men cannot amount to anything nor taste of the fountain of goodness unless they do this under the persuasion of ladies… It is clear that every man should strive with all his might to be of service to ladies so that he may shine by their grace. But ladies are greatly obligated to keeping the hearts of good men set upon doing good deeds and to honor every man according to his deserts. For whatever good things living men may say or do, they generally credit them all to to the praise of women, and by serving women they so act that they may pride themselves on the rewards they receive from them, and without these rewards no man can be of use in this life or be considered worthy of any praise. Now I know many men who are sure they have been given perfect love, and I know others who are maintained only by the milk of nourishing hope; but I, who have neither perfect love nor the gift of hope, am more sustained merely by the pure thought of you, which I do have, than all other lovers are by unnumbered solaces. May your pity therefore turn and regard my solitary thought and give it a little increase. And truly I beg you must earnestly not try to keep away from Love’s court, for those who stay away from the palace of Love live for themselves alone, and no one gets any profit from their lives…

THE WOMAN SAYS: Although your words are deep and profound and reach to the walls of Love’s subtlety, I shall try, as far as I am able, to give them a fitting answer. And because the experience of Cicero tells us that the things which are said last in a discourse are more readily retained in the memory, I shall try to answer your last remarks first. Now your urging me to strive to do what might increase my good character and that of others was pleasing and acceptable enough to me, because I had it in my heart to do that without advice from anyone. And I know women should, as you have asserted, be the cause and origin of good things… and should persuade every man to do courteous deeds and to avoid everything that has the appearance of boorishness and not to be so tenacious of his own property as to blacken his good name. But to show love is to gravely offend God and to prepare for many the perils of death. And besides it seems to bring innumerable pains to the lovers themselves and to cause them constant torments every day… I myself have had no experience in love and so naturally I can tell you nothing about its nature except so far as I have learned about it from what others tell me.

THE MAN SAYS: It is the pure love which binds together the hearts of two lovers with feelings of delight. This kind consists in the contemplation of the mind and the affection of the heart; it goes as far as the kiss and the embrace and the modest contact with the nude lover, omitting the final solace. . . . But that is called mixed love which gets its effect from every delight of the flesh and culminates in the final act of Venus. . . . This kind quickly fails, and one often regrets having practiced it; by it one’s neighbor is injured, the Heavenly King is offended, and from it come very grave dangers. But I do not say this as though I meant to condemn mixed love, I merely wish to show which of the two is preferable. But mixed love, too, is real love, and it is praiseworthy, and we say that it is the source of all good things, although from it grave dangers threaten, too. Therefore I approve of both pure love and mixed love, but I prefer to practice pure love. . . .

THE WOMAN SAYS: Since a certain woman of the most excellent character wished to reject one of her two suitors by letting him make his own choice, and to accept the other, she divided the solaces of love in her in this fashion. She said, “Let one of you choose the upper half of me, and let the other suitor have the lower half.” Without a moment’s delay each of them chose his part, and each insisted that he had chosen the better part. . . . I ask you which seems to you to have made the more praiseworthy choice.

THE MAN SAYS: Who doubts that the man who chooses the solaces of the upper part should be preferred to the one who seeks the lower? For so far as the solaces of the lower part go, we are in no wise differentiated from brute beasts; but in this respect nature joins us to them. But the solaces of the upper part are, so to speak, attributes peculiar to the nature of man and are by this same nature denied to all the other animals. Therefore the unworthy man who chooses the lower part should be driven out from love just as though he were a dog, and he who chooses the upper part should be accepted as one who honors nature. Besides this, no man has ever been found who was tired of the solaces of the upper part, or satiated by practicing them, but the delight of the lower part quickly palls upon those who practice it, and it makes them repent of what they have done.

From Book II of The Art of Courtly Love, entitled “How Love May be Retained,” I shall quote only a few of the 31 “rules of love which the King of Love himself, with his own mouth, pronounced for lovers”:

1. Marriage is no real excuse for not loving.

2. He who is not jealous cannot love.

10. Love is always a stranger in the home of avarice.

11. It is not proper to love any woman whom one should be ashamed to seek to marry.

13. When made public, love rarely endures.

14. The easy attainment of love makes it of little value; difficulty of attainment makes it prized.

15. Every lover regularly turns pale in the presence of his beloved.

16. When a lover suddenly catches sight of his beloved his heart palpitates.

17. A new love puts to flight an old one.

19. If love diminishes, it quickly fails and rarely revives.

20. A man in love is always apprehensive.

21. Real jealousy always increases the feeling of love.

22. Jealousy, and therefore love, are increased when one suspects his beloved.

23. He whom the thought of love vexes, eats and sleeps very little.

27. A lover can never have enough of the solaces of his beloved.

28. A slight presumption causes a lover to suspect his beloved.

29. A true lover is constantly and without intermission possessed by the thought of his beloved.

Primary source: Andreas Capellanus, The Art of Courtly Love, translated by John Jay Parry (New York, Columbia University Press, 1941). [FULL TEXT]

Some introductory remarks above by Peter G. Beidler, – from Backgrounds to Chaucer,

1. GENERAL DEFINITION OF GYNOCENTRISM (Greek: “female” + Latin: “centrum”)

(a). n. Dominant or exclusive focus on women in theory or practice; or to the advocacy of this. Often practiced to the detriment of males.

(b). n. A dominant focus on women’s needs and wants relative to men’s needs and wants. This can happen in the context of academic research, institutional policies, cultural conventions, and in gendered relationships.

(c). adj. Anything can be considered gynocentric when it is concerned exclusively with a female (or specifically a feminist) point of view.

2. SOCIOLOGY

(a). A pervasive cultural complex geared to prioritizing women and their interests.

(b). A reference to individual gynocentric acts or events (eg. Mother’s Day).

3. BIOLOGY

(a). The biological theory that humans prioritize female reproductive capacity.

4. PSYCHOLOGY

(a). An exclusive focus on the psychological experiences, emotions, needs and wants of women.

(b). Gynocentrism refers to a female expression of narcissism operating within the limiting context of heterosexual relationships and exchanges.

____________________________

DICTIONARY DEFINITIONS:

ALLWORDS.COM

Gynocentrism: An ideological focus on females, and issues affecting them, possibly to the detriment of non-females. Contrast with androcentrism.

MIRRIAM-WEBSTER

Gynocentrism: Dominated by or emphasizing female interests or a female point of view.

DICTIONARY.COM

Gynocentrism: Focused on women; concerned with only women.

OXFORD DICTIONARY

Gynocentrism: centred on or concerned exclusively with women; taking a female (or specifically a feminist) point of view.

FARLEX DICTIONARY

Gynocentrism: Female-oriented, -centered, -exclusiveness. Sexism , discrimination on the basis of sex.

ENCYCLOPEDIA.COM

A radical feminist discourse that champions woman-centered beliefs, identities, and social organization.

EARLIEST MENTIONS OF GYNOCENTRISM

Etymology dictionaries do not record the history and earliest usage of the term gynocentrism. My own search reveals that gynocentrism has been in use since at least as early as the 1800s. Here are a few early references to gynocentrism and gynocentric:

_______________________________________________________

The Open Court, Volume 11 (Open Court Publishing Company, 1897)

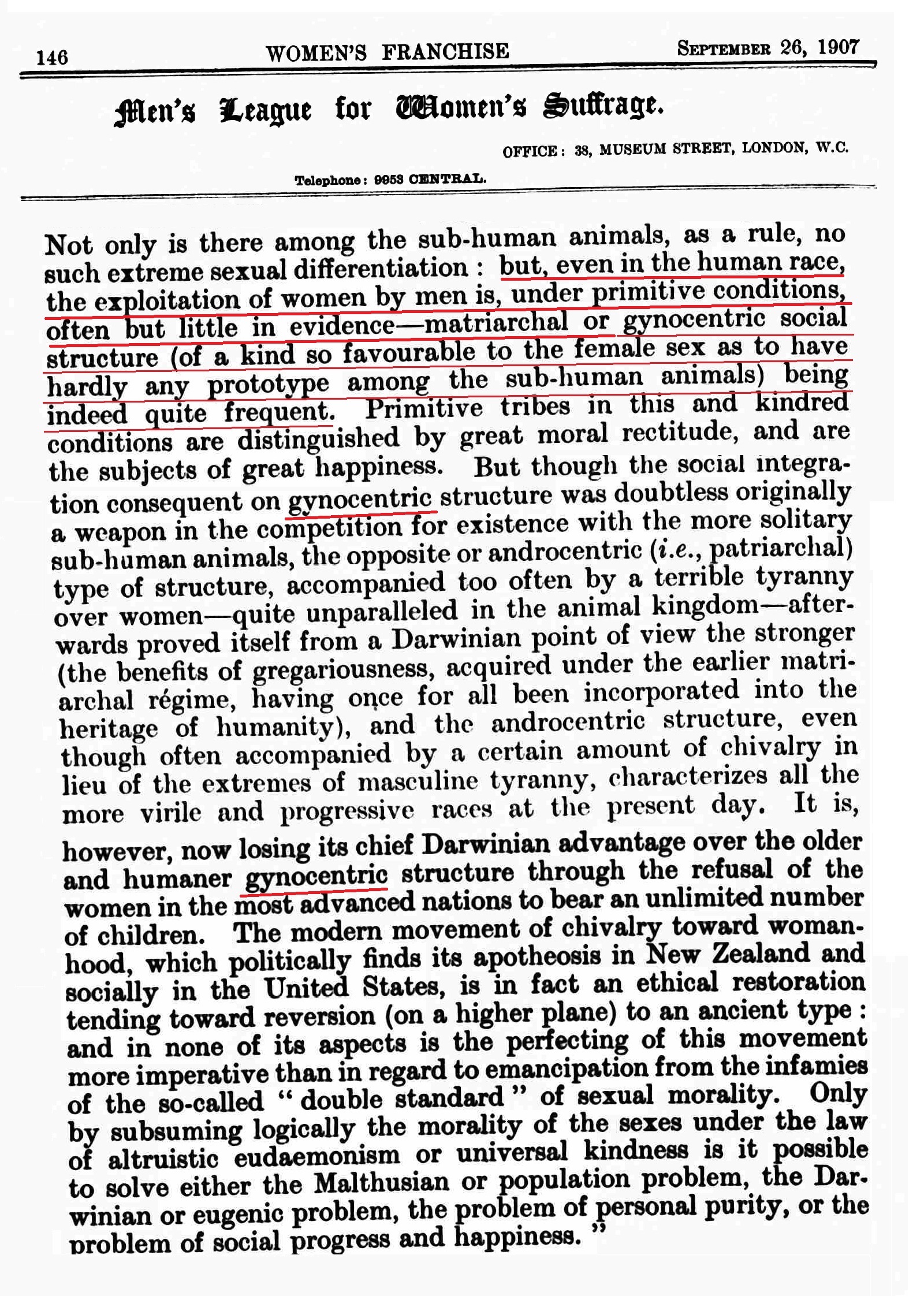

Women’s Franchise Newspaper (New Zealand, Thurs 26 November 1907)

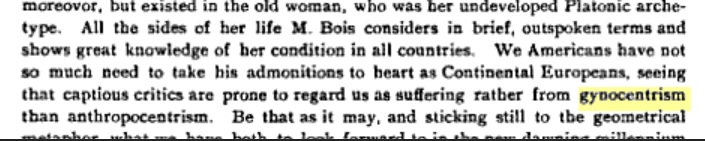

The Independent, Volume 67, Issues 3175-3187 (Independent Publications, incorporated, 1909)

![]()

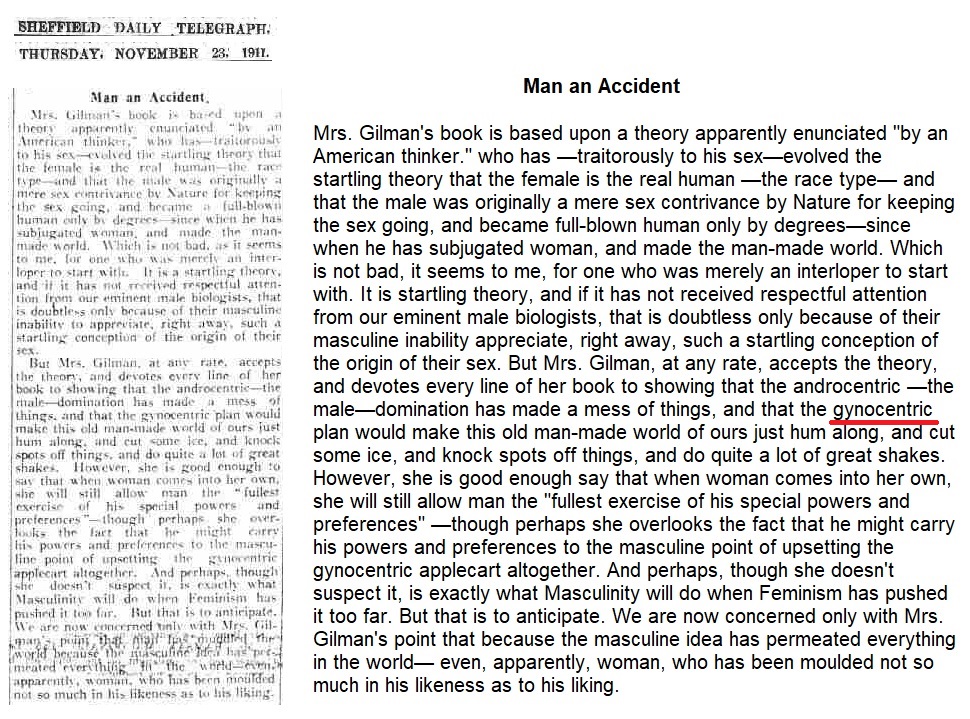

Sheffield Daily Telegraph – (Thurs 23rd November 1911)

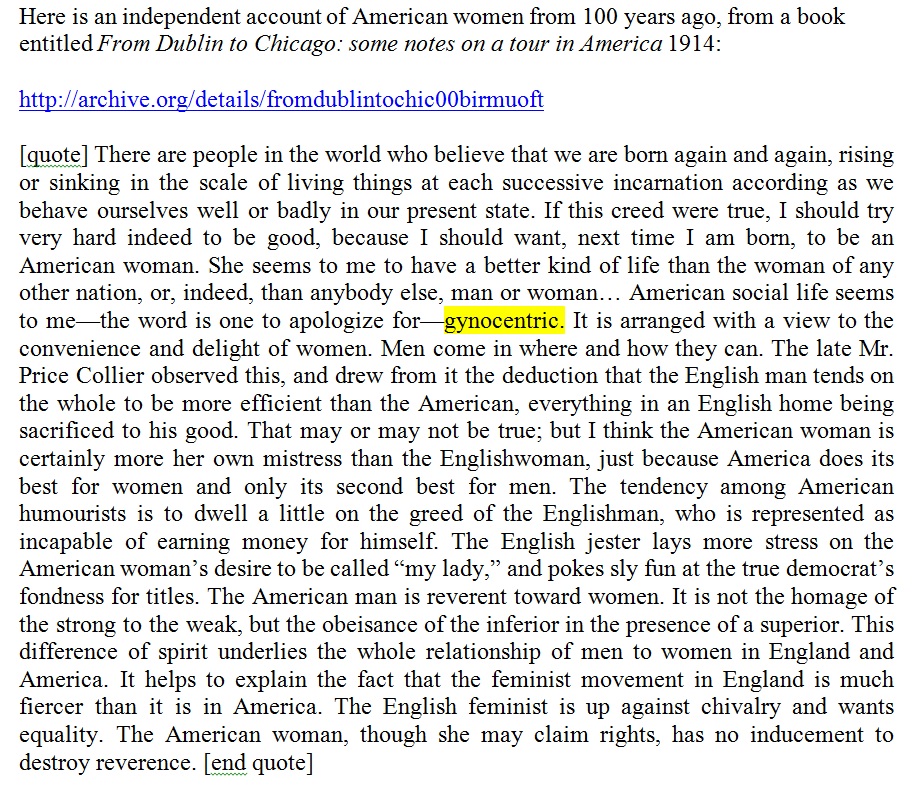

From Dublin to Chicago: Some Notes on a Tour in America (George H. Doran Company, 1914)

![]()

FULL-TEXT:

________________________________________________________

Gynocentrism continued to be used throughout the nineteenth century and into the present with a stable meaning of female centered, especially to a culture so disposed wherein, “It is arranged with a view to the convenience and delight of women. Men come in where and how they can.” [1914 -see above]

The word is employed infrequently, perhaps due to the availability of simpler phrasings such as ‘woman centered’ or ‘female dominated.’ When employed it appears to be viewed by writers as a self-explanatory term not requiring further definition.

***

RELATED WORDS:

The following are a few early uses of the words Gynarchy, Gynocracy, Gynæcocracy, Gynocrat, and Gyneolatry which are employed variously to refer to female power or hegemony in political, social, family, or gender contexts. Note the mention from 1660 below in which gynarchy is used to refer to the gender context where the wife is not subject to, but rather superior to the husband. Similarly, gynocracy which is sometimes defined as “petticoat government” applies to both female dominance of the social order and to female dominance in gender relations; eg. individual men are referred to as “petticoat governed” (see petticoat government at bottom).

Gynarchy:

Gynæcocracy:

The following mention of gynæcocracy is from the volume;

An Universal Etymological English Dictionary printed in 1737

Note that gynæcocracy is defined as “Petticoat Government”

From the Dictionary of the English Language 1755

Gynocracy:

Gynocracy in ‘Letters to and from Jonathan Swift’ printed in 1741.

Note again the reference to Petticoat Government

This mention from the Dictionary of Arts and Sciences from 1763.

This one from ‘The Gentleman’s Magazine’ of 1838.

Newspaper article ‘A Dethroned Tyrant’ of 1902.

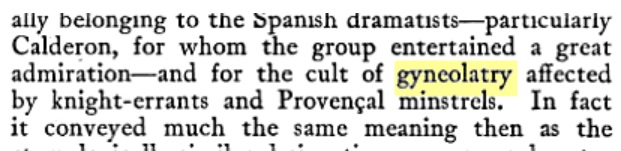

Gyneolatry:

Book Chat, Volumes 3-4 (Brentano Bros., 1888)

The Life and Works of Friedrich Schiller (H. Holt, 1901)

The Athenæum, vol 2 (British Periodicals Limited, 1909)

Zones of the spirit: a book of thoughts (G.P. Putnam, 1913)

The Collected Works, Volume 1 (Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1924)

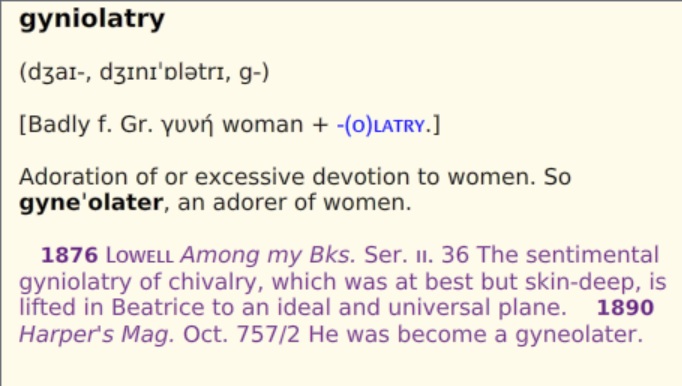

Oxford Dictionary entry for Gyniolatry

Petticoat Government:

By Jason Gregory

I admit it. I have a guilty pleasure—feminist-philosophers. No, feminist-philosophers are not necessarily oxymoronic, though some of them are moronic. Take, for example, Iris M. Young.

Young studied philosophy and earned a doctorate in philosophy from Pennsylvania State University. She became a professor of political science and was well known for her work in “theories of justice, democratic theory and feminist theory.” Sadly, Young lost a battle with cancer in 2006 and the world was deprived of “one of the most important feminist thinkers in the world…one of the most important political philosophers of the past quarter century.”

While researching this much respected philosopher, I discovered one of her papers, “Humanism, Gynocentrism, and Feminist Politics.” It is a brilliant and fascinating paper. It is a must read for anybody interested in The Patriarchy™, gender politics, and philosophy.

In this paper, Young presents two remarkably different versions of feminism—humanist-feminism and gynocentric-feminism. Young admits that these two types of feminisms are often contrary to and sometimes contradictory with each other. She also admits that both feminisms share the common narrative thread of male-as-antagonist. The overarching antagonist to both narratives is the male dominated culture that oppresses women—The Patriarchy™.

This antagonist represents weak and lazy writing. It’s a tired, uninspiring, and one-dimensional villain. This antagonist no longer has a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith. The Patriarchy™ is the Snidely Whiplash of feminist narratives—a cartoonish caricature of evil, the archenemy of all women, humanity, and civilization. It is not an artifact of “poetic faith.”

This antagonist represents weak and lazy writing. It’s a tired, uninspiring, and one-dimensional villain. This antagonist no longer has a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith. The Patriarchy™ is the Snidely Whiplash of feminist narratives—a cartoonish caricature of evil, the archenemy of all women, humanity, and civilization. It is not an artifact of “poetic faith.”

As such, The Patriarchy™ is not a real thing. It is only an imagined thing—a fetishized object of imagination that exists in the minds of feminists and other morons. It exists to perpetuate a shallow and one-dimensional narrative that presents women as objects-of-victimization. It is the sort of thing that feminists love to hate. It is loved because it can be blamed for everything. It is hated because it is the villain. Without The Patriarchy™, there would be no feminist narratives. Without Snidely Whiplash, there would be no Dudley Do-Right. The Patriarchy™ is one half of a shallow and one-dimensional dichotomy of good vs. evil that exists in feminist narratives. It’s not any real thing of lived-experience. It is only an imaginary thing of imagined-experience.

To better understand this shallow dichotomy and the silliness of feminist narratives, let’s look at two of the most significant and influential feminist narratives as presented by Iris M. Young. Both narratives present women as victims of The Patriarchy™. Both narratives present The Patriarchy™ as an antagonist, a villain like Snidely Whiplash who twiddles his moustache and has no human depth beyond a sadistic lust for the devaluing and disempowerment of women.

Humanist-feminism

Humanist-feminism, according to Young, is best described in the works of Simone de Beauvoir. At its core is a revolt against being imprisoned in femininity. For them The Patriarchy™ “has ascribed to women a distinct feminine nature by which it has justified the exclusion of women from most of the important and creative activity of society—science, politics, invention, industry, commerce, the arts.” By rejecting such femininity, humanist-feminism delivered a revolt against The Patriarchy™ itself.

What makes this Beauvoirian revolt so fascinating is the fact that it is founded theoretically on the philosophical distinction between immanence and transcendence. Immanence roughly designates being an object. Transcendence roughly designates being a free-subject that defines its own nature and “makes projects that bring new entities into the world.”

It is argued by humanist-feminists that The Patriarchy™ does not allow women to become such transcendent and free-subjects. Instead, women are relegated to being objects of domestic and sexual service to men and for the benefit of men. As such, the full humanity of women is restricted by The Patriarchy™. This is, according to humanist-feminists, a brutalization of the personhood of half the human race for benefit to the other half. The Patriarchy™ mutilates and deforms women into objects—the non-human Other. Young writes that this “distinction between transcendence and immanence ensnares Beauvoir in the very definition of woman as a non-human Other…”

By defining humanity as transcendence, as a free-subjectivity above mere life and the processes of nature that repeat in endless cycles, women can only exist as victims—“maimed, mutilated, dependent, confined to a life of immanence and forced to be an object.” In short, humanity transcends, but women are imprisoned to a life of immanence. Humanist-feminism was a revolt against this sort of immanence, reproductive biology, domestic concerns, and motherhood—the things Beauvoir found most oppressive to women.

As such, Beauvoirians devalue women…just like The Patriarchy™ devalues women. The humanist-feminist revolt against The Patriarchy™ is patriarchal. As such, humanist-feminism is The Patriarchy™. They smash The Patriarchy™ by being it.

Gynocentric-feminism

According to Young, “gynocentric feminism defines the oppression of women very differently from humanist feminism. Women’s oppression consists not of being prevented from participating in full humanity, but of the denial and devaluation of specifically feminine virtues and activities by an overly instrumentalized and authoritarian masculinist culture.” Gynocentric-feminism is not a revolt against femininity. It is a revolt against the devaluation of femininity. It is a revolt against The Patriarchy™ by embracing what The Patriarchy™ always “ascribed” to women. As such, gynocentric-feminism is The Patriarchy™.

For gynocentric-feminists, femininity is “not the problem, not the source of women’s oppression, but indeed within traditional femininity lie the values that we should promote for a better society. Women’s oppression consists of the devaluation and repression of women’s nature and female activity by the patriarchal culture.” Again, The Patriarchy™ is still to blame because it “threaten[s] the survival of the planet and the human race. [Patriarchal] values exalt death, violence, competition, selfishness, a repression of the body, sexuality, and affectivity.”

According to Young, The Patriarchy™ produces “phallogocentric categorization,” a moral rationality and language of sharp distinctions, of abstract rights and justice. However, the feminine is supposed to produce loose categories, a flowing of language that envelops and folds in on itself, reflects itself in a continuous and particularistic ethics of care—a continuous flowing of garbled gibberish. The feminine virtue is supposed to place the particular over the abstract and universal, all the while denying the “nature/culture dichotomy held by humanists… [asserting] the connection of women and nature,” rooting the feminine in the body-experience, rather than in some sort of abstract transcendence.

Gynocentric-feminism places a high value on the woman’s reproductive processes. It is supposed that these processes give women a “living continuity with their offspring that it does not give men. Women thus have a temporal consciousness that is continuous, whereas male temporal consciousness is discontinuous.” As such, males are said to be more alienated from their children, but more connected to their work and other endeavors of artifact creation. In this way, being woman is not being an object. Bringing forth life into this world is one of the most important endeavors-of-creation…and only women can do that.

Gynocentric-feminism inverts humanist-feminism—completely upending prior notions of women’s oppression. Yet, smashing The Patriarchy™ remains a goal of gynocentric-feminism. They smash The Patriarchy™ by embracing it.

Implications

Where humanist-feminism destroyed the value of the feminine, gynocentric-feminism restores it. There is dignity for women within their bodies and within their uniquely female body-experiences. Gynocentric-feminism shows that this connection with the body produces uniquely feminine virtues, language, and experiences of which men are not privy. In fact, men are not privileged at all in this way. Men are alienated from these experiences, from a “living continuity” with their children, and relegated to such experiences by proxy—through intellectual creations, hierarchal competition, and through functioning as an object-of-utility for a woman, for women, and for society-in-general.

This reality requires a reassessment of what male privilege means. Young writes, “If we claim that masculinity distorts men more than it contributes to their self-development and capacities, again, the claim that women are the victims of injustice loses considerable force.” She eventually questions, “what warrants the claim that women need liberating…of what does male privilege consist?” She has difficulty swallowing that bitter red pill. She has difficulty being straight and saying that we’ve been wrong about The Patriarchy™ and male privilege.

Although, she never disavows patriarchy theory, she does put forth a clever analogy as a way to try and change the subject, to escape responsibility, yet still fetishize and blame The Patriarchy™. In regards to gender, Young states that “we need a conception of difference that is less like the icing bordering the layers of cake and more like a  marble cake, in which the flavors remain recognizably different but thoroughly insinuated in one another. [And this]… social change requires changing the subject, which in turn means developing new ways of speaking, writing, and imagining.”

marble cake, in which the flavors remain recognizably different but thoroughly insinuated in one another. [And this]… social change requires changing the subject, which in turn means developing new ways of speaking, writing, and imagining.”

Translation

Young wants to have her cake and eat it too. She wants to change the subject and direct attention away from the wrongheaded notions about male privilege and female oppression. She wants to create a narrative in which female oppression and privilege simultaneously exist in one swirl of garbled gibberish — a marble cake. She does not come forward to clearly say, “Oops, we were wrong about male privilege and The Patriarchy™.” She does not apologize for the decades of bashing and shaming men about their so-called privilege. She makes no apologies for the centuries of oppression men have endured as objects-of-utility for women and for society-in-general. She does not make any apologies for wanting her cake and eating it too.

Young is playing a game, essentially saying “it’s the fault of The Patriarchy™ that we were wrong…even though we weren’t really wrong. The Patriarchy™ forced feminists to make distinct icing and borders on their narrative-cake. It’s the fault of The Patriarchy™ that feminists didn’t create a marble-cake-narrative in which women could be simultaneously oppressed and liberated, thoroughly insinuated in one another. It’s the fault of The Patriarchy™ that The Patriarchy™ was allowed to be the primary antagonist of any feminist narrative.” This is Young’s elaborate game of victim-blaming.

Why did you men allow us to blame you? It’s your fault that we falsely accused you. Had you men simply valued us women, we would never have falsely accused you men of oppressing us. Never mind the countless bodies of men who sacrificed their lives for women and for society-in-general; that’s oppression of women too. Valuing us is not-valuing us. Oppressing us is not-oppressing us. No matter what men do, it’s the fault of men that women are simultaneously liberated and oppressed, valued and not-valued, empowered and not-empowered. Men and by extension, The Patriarchy™, are to blame for everything.

Conclusion

Young, like most feminists, clings to her fetish—her imagined-experience of The Patriarchy™. She refuses to develop a more comprehensive narrative. She refuses to create a narrative that gives depth to the lived-experiences of men. She refuses to relinquish her hatred of men. She prefers blaming men for everything. This is her love, her hatred, and her fetish. She clung to these until death.

Sadly, this is what makes Young’s paper so brilliant and fascinating. It illustrates the grasp of this fetish—The Patriarchy™. A philosopher as clever as Young fails to relinquish her fetish. Even after clearly making the case that prior notions of The Patriarchy™ and male privilege were wrong, she maintains that men are still to blame. Even when she knows that it’s not the fault of men, she still blames men—The Patriarchy™.

By painting men as The Patriarchy™, men can be made a cartoonish caricature of evil. Men become as shallow and one-dimensional as Snidely Whiplash—the archenemy of women, humanity, civilization, and all things good. Men become The Patriarchy™, the non-human Other.

This is the narrative of feminisms. This is the common thread that binds together feminist narratives. This is the dehumanization of men as the antagonist. It is the fetishizing of men as The Patriarchy™–an imagined thing, a fetishized object of imagination, a villain.

This villain no longer inspires the “willing suspension of disbelief.” This villain is not an artifact of “poetic faith.” This villain represents weak and lazy writing. The Patriarchy™ is bad literature…and so are feminist narratives.

The way forward may be some sort of “marble cake,” as Young describes, where gender differences are distinct, yet thoroughly insinuated within each other. However, before that can happen, a narrative granting multi-dimensionality and depth to men is needed. A narrative consisting of compassion and consideration for the lived-experiences of men and boys is needed. That will never happen as a feminist narrative. So long as men are written as the antagonist, as The Patriarchy™, men will always be the Other–the icing on the outside, apart from the cake, apart from humanity.