Por Peter Wright & Paul Elam

Muchos estudiosos de las políticas sexuales plantean la noción “científica” de que nuestra cultura ginocéntrica es una realidad biológica básica, y que tenemos dos opciones: o bien seguimos el programa y disfrutamos, o bien nos retiramos del sistema de manera nihilista.

Una explicación alternativa del superestimulo sugiere que se trata simplemente de una exageración del potencial humano; una exageración que lleva al fracaso social y reproductivo, pese a la sabiduría popular.

El léxico de las biociencias nos puede resultar útil para entenderlo.

Por ejemplo, en el caso de los pájaros hembra, prefieren incubar huevos artificiales de mayor tamaño, en vez de sus propios huevos naturales.

Por ejemplo, en el caso de los pájaros hembra, prefieren incubar huevos artificiales de mayor tamaño, en vez de sus propios huevos naturales.

Los huevos grandes y coloridos son un superestímulo. El hecho de dejar desamparados los huevos auténticos es la superrespuesta.

De una forma similar, los seres humanos también son engañados con facilidad por los vendedores de comida basura. Es muy sencillo entrenar a los seres humanos para que elijan productos que provocan enfermedades cardiacas, diabetes y cáncer, en vez de los alimentos nutritivos para cuyo consumo y aprovechamiento han evolucionado; sólo hacen falta unos cuantos trucos con las papilas gustativas y los reflejos de hambre.

El azúcar y los carbohidratos refinados son superestímulos. El consumo de sustancias tóxicas es la superrespuesta.

La idea es que el comportamiento humano saludable evolucionó en respuesta a estímulos normales en el entorno natural de nuestros ancestros. Eso incluye nuestros instintos reproductivos. Esas mismas respuestas de conducta ahora han sido secuestradas por el estímulo supernormal1.

Desde este punto de vista, podemos ver que el superestímulo actúa como una droga potente, perfectamente comparable con la heroína o la cocaína, que imitan sustancias químicas más débiles, como la dopamina, la oxitocina y las endorfinas, todas ellas presente de manera natural en el cuerpo.

Como ocurre con la drogadicción, los efectos de los superestímulos son responsables de toda una serie de obsesiones y fracasos que afectan al hombre moderno: desde la epidemia de la obesidad y la obsesión con la territorialidad hasta los comportamientos destructivos, violentos y suicidas fundamentales en nuestro culto moderno al amor romántico.

Un detalle interesante sobre los superestímulos de los narcóticos artificiales es el fenómeno conocido como “la caza del dragón”. Es un término que surgió en los fumaderos de opio de China, y se refiere a lo que ocurre la primera vez que una persona inhala el vapor del opio. La euforia resultante es absoluta e incluso mágica… la primera vez.

Después, el consumidor intenta recrear ese subidón maravilloso, una y otra vez, con cantidades cada vez mayores de droga. Pero no puede. El cerebro ya se ha acostumbrado a la inundación de opiáceos artificiales. El consumidor se coloca y se vuelve adicto, pero la magia de la primera experiencia es una mariposa esquiva.

Pero la persiguen con todas sus fuerzas, tratando de cazar al dragón sobre el que cabalgaron en su primera experiencia.

Podemos ver un fenómeno similar en los hombres que, en sus relaciones con las mujeres, intentan desesperadamente ser recompensados con amor, sexo y aprobación, mediante el uso de la caballerosidad romántica. Como drogadictos, avanzan por una banda de Möbius, caminan en círculos, persiguiendo al dragón.

En nuestra opinión, no hay duda de cómo se produce esto.

A continuación presentamos tres ejemplos de superestímulos humanos, y cómo se utilizan para desencadenar una superrespuesta destructiva en el hombre.

- Neotenia fabricada artificialmente

La neotenia es la retención de las características infantiles en el cuerpo, la voz o los rasgos faciales. En el ser humano, la neotenia activa lo que se conoce como cerebro parental: un estado de la actividad cerebral que fomenta la nutrición y los cuidados. Esa activación se produce mediante el llamado mecanismo de liberación innato.

Un ejemplo clásico de mecanismo de liberación innato es el que tiene lugar cuando los polluelos de gaviota dan picotazos en el pico de sus padres para conseguir comida.

Todas las gaviotas adultas tienen una mancha roja en la parte inferior del pico; cuando la ven los polluelos, se desencadena, o libera, el instinto de darle un picotazo. Se trata del mecanismo de liberación innato.

Desde luego, este mecanismo de liberación innato es vital para la supervivencia de las gaviotas, y en todas las especies de aves y de mamíferos (y en cualquier criatura a la que le preocupe su descendencia) existe algo similar. En los mamíferos, el infantilismo es uno de los mecanismos de liberación innatos que determinan, de forma inconsciente, nuestra motivación para proteger y proveer, garantizando así la supervivencia de la especie.

Sin embargo, las características infantiles humanas también se pueden manipular para obtener atenciones y apoyo que sobrepasen con mucho las necesidades de supervivencia.

En concreto, la mujer utiliza la neotenia para conseguir distintas ventajas, un hecho que no pasa desapercibido a la escritora y médica Esther Vilar, que escribe lo siguiente:

“El mayor ideal de la mujer es una vida sin trabajo ni responsabilidades. Pero, ¿quién lleva esa vida, aparte de un niño? Un niño de mirada suplicante, de cuerpo pequeño y gracioso, con hoyuelos, rellenito y de piel clara y tersa; un adulto en miniatura de lo más adorable. Es al niño a quien imita la mujer: su risa fácil, su indefensión, su necesidad de protección. Es necesario cuidar del niño, porque no puede valerse por sí mismo. ¿Y qué especie no cuida instintivamente de su descendencia? Debe hacerlo, si no quiere que la especia se extinga.

Con la ayuda de cosméticos hábilmente aplicados, diseñados para preservar ese preciado aspecto de bebé; con exclamaciones indefensas como “Uuuh” y “Aaah”, que denotan asombro, sorpresa y admiración en una conversación dulce y trivial, la mujer preserva ese aspecto de bebé durante el mayor tiempo posible, para que el mundo siga creyendo en la adorable y dulce niñita que fue antaño, y confía en que el instinto protector del hombre lo obligue a cuidar de ella.”2

El zoólgo Konrad Lorenz descubrió que las imágenes de cabezas redondeadas y con ojos grandes (izquierda) liberan reacciones parentales en un amplio espectro de especies mamíferas, en contraste con las cabezas anguladas y con ojos proporcionalmente más pequeño, que no provocan dichas respuestas.

Comparemos las imágenes de Lorenz de la izquierda con imágenes de maquillaje para los ojos (arriba), hábilmente aplicado por la mujer moderna en busca de amor. Las sombras de ojos, delineadores y rímeles de todos los colores, por no mencionar las horas practicando ante el espejo, abriendo los ojos al máximo y agitando las pestañas; todo está diseñado para estimular y activar los “paleo-reflejos” del espectador.

Los rostros femeninos neoténicos (ojos grandes, gran distancia entre los ojos, nariz pequeña) les resultan más atractivos a los hombres, mientras que los rostros menos neoténicos se consideran los menos atractivos, independientemente de la edad real de la mujer3. Y de todos estos rasgos, los ojos grandes son el indicio neoténico más eficaz4; se trata de una fórmula triunfal que ha sido utilizada en el anime y en los personajes de Disney, exagerando el tamaño de los ojos e infantilizando el rostro de la mujer adulta.

- Exageración de las cualidades sexuales

La vestimenta y las posturas corporales que realzan las caderas, los muslos, los traseros y los senos llevan milenios desarrollándose.

El corte, el color y la caída de las prendas; la ropa interior, los corsés, la lencería y los zapatos, sombreros, joyas y otros accesorios nos permitirían realizar un largo estudio sobre la evolución de la moda, y en términos de sexualidad, representan superestímulos diseñados para desatar una sobrecarga de atracción sexual en el espectador.

En relación con el “realzamiento”, resulta muy interesante la aparición de la cirugía plástica, pensada para transformar el cuerpo en un escenario de superestímulos, a veces con resultados grotescos e incluso letales. Esos son los riesgos que se corren y se aceptan al ir en pos de un atractivo sexual aumentado.

Implantes de pecho, implantes de glúteos, rinoplastias, abdominoplastias, lifting facial… todo ello diseñado para aumentar la sexualidad y, aún más importante, aumentar el poder y el control.

- Instinto de emparejamiento intensificado artificialmente

Todos hemos escuchado el consejo de la matrona experimentada a las mujeres más jóvenes: “Si les dais vuestro amor incondicionalmente, perderán el interés; privadles de un poco de afecto y los tendréis siempre suplicando que les deis más”.

Hoy en día, este mensaje está tan difundido que se están reutilizando técnicas de adiestramiento de animales para las mujeres que desean controlar las necesidades afectivas de los hombres. En Cómo hacer que tu hombre se comporte en 21 días o menos utilizando los secretos de los adiestradores caninos profesionales, podemos leer lo siguiente:

“Un perro siempre se porta mejor cuando quiere que lo alimentes. Después se vuelve un manojo de nervios. Un truco muy conocido para que el perro mantenga su mejor comportamiento consiste en llenar su comedero únicamente hasta la mitad, para que desee más.

Ocurre lo mismo con su hambre de afecto. Mantenlo siempre emocionalmente hambriento de ti, y será más atento y fácil de controlar.”

Por cruel que suene, la privación de afecto, sexo, aprobación y amor se ha convertido en otra herramienta del repertorio femenino de superestímulos, empleados para obtener por la fuerza el servicio del hombre. Es posible que hubiera una época en la que ese servicio se pudiese considerar una respuesta apropiada a un estímulo de supervivencia. Sin embargo, hoy en día ha sido sustituido por superestímulos, y el servicio masculino ha degenerado en una superrespuesta destructiva.

Esta clase de consejos amorosos para mujeres abunda en Internet. Pretenden intensificar el deseo del hombre, de manera que la obtención de un vínculo estable (algo necesario en una relación sana) se convierta en una meta, en un objetivo. Pero el juego de la caballerosidad romántica, como todos los juegos de feria, está amañado. La meta está siempre fuera de nuestro alcance.

La necesidad de amor, aceptación y seguridad del hombre, una necesidad humana básica, se ve frustrada, dejándolo inmerso en un ciclo permanente de privaciones.

De hecho, uno de los principios fundamentales del amor romántico consiste en mantener el vínculo amoroso en un halo de negación prometedora y tentadora, y en mantener al hombre siempre listo para ser manipulado y utilizado.

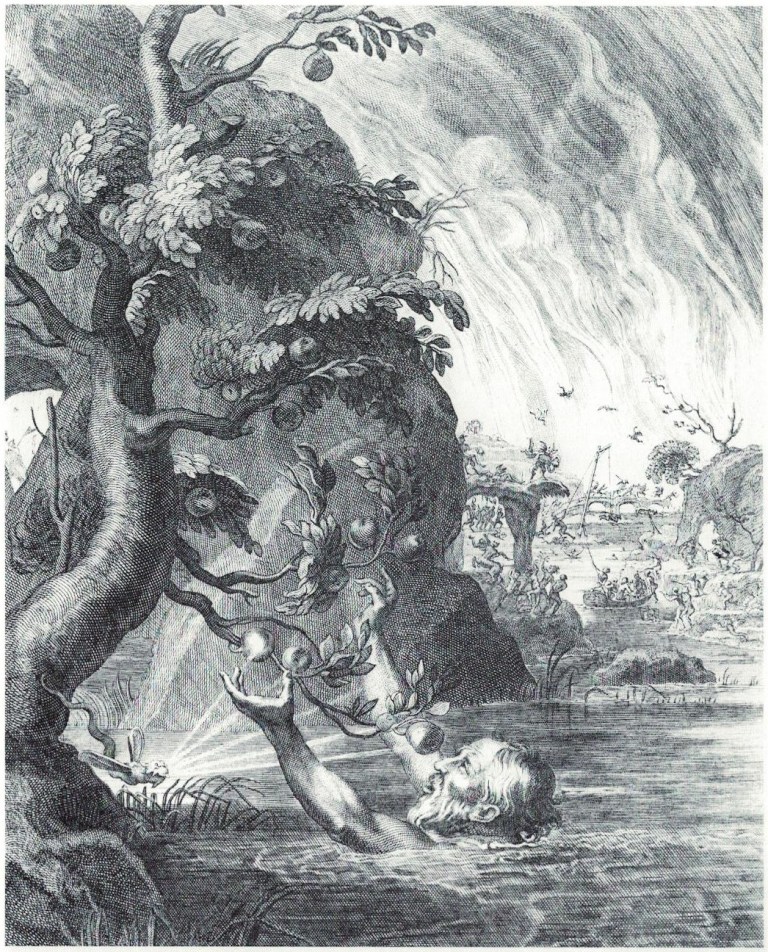

La palabra tantalizing (“tentador”) proviene de la historia griega de Tántalo. Éste, según nos cuenta la leyenda, ofendió a los dioses. Su castigo consistió en ser colocado en medio de un río, con el agua hasta el cuello. Hacia él se inclinaba un manzano cargado de manzanas rojas y maduras.

Los dioses lo castigaron con una sed y un hambre feroces. Cuando inclinaba la cabeza para saciar la sed, las aguas retrocedían. Del mismo modo, cuando alargaba el brazo para tomar una manzana, la rama ascendía, quedando fuera de su alcance.

Las mujeres son socializadas para tentar a los hombres con la posibilidad de un emparejamiento, para mantener el fruto del amor siempre fuera de su alcance, y para enturbiar aún más las aguas con los dictados de la caballerosidad romántica.

Si quieres ese vínculo de pareja, es decir, si quieres que te tienten más, más te vale recibirla con flores, abrirle la puerta y, evidentemente, pagar la cuenta.

Más te vale estar listo para vivir así el resto de tu vida, exiliado en el río con Tántalo, eternamente sediento y hambriento. Hoy en día, el simple afecto se ha transformado en algo muy complejo, un impulso que ahora está guiado por las costumbres de la caballerosidad romántica, diseñadas para otorgarle el máximo poder a la mujer.

Incluso cuando en principio ya se ha establecido el vínculo de pareja, es posible que te sigan privando de amor, sexo y aprobación como método de control. Puede ser incluso peor después de haberse emparejado que durante el proceso de cortejo.

Ese comportamiento femenino no es un reflejo innato y simple; es un reflejo en el que han sido educadas y socializadas culturalmente. La mayor parte de las niñas dominan el juego de la inclusión y la exclusión, en grupos o con sus amigas, mucho antes de cumplir 10 años, y las meta-normas que han aprendido vuelven a aparecer en los consejos amorosos populares;se trata de normas diseñadas para perturbar la seguridad afectiva de la que nosotros, como seres gregarios, disfrutaríamos en caso de no haber manipulación.

Las normas femeninas resuenan abiertamente a lo largo de todo un género literario:

- Mantén un aire de misterio.

- Esfuérzate únicamente al 30%.

- Haz que sea él quien vaya a ti.

- No te veas con él sin una semana de antelación.

- No lo llames nunca, salvo para devolverle su llamada.

- Nunca respondas inmediatamente a una llamada o a un mensaje.

- Haz que sea él el que se acerque a ti.

- No le devuelvas la llamada inmediatamente. Eres una chica solicitada.

- Finaliza la llamada SIEMPRE a los 15 minutos (aunque no te guste. Así te llamará más).

- Aunque no estés ocupada, finge que lo estás.

Hemos recopilado estos consejos tras un examen somero de únicamente dos páginas web con consejos amorosos para la mujer. Sin embargo, no son producto de la era de la información. Representan la expresión extensa y codificada de lo que se ha enseñado a las mujeres de generación en generación, desde el surgimiento de la caballerosidad romántica.

Son las bases de un adiestramiento para la obediencia, pensado para programar al hombre caballeroso y romántico; son superestímulos, tremendamente eficaces a la hora de provocar una superrespuesta. En esta caso, la adulación ciega y servil por parte de un hombre débil y poco introspectivo.

El Amor Romántico

El amor romántico se puede reconceptualizar como un conjunto de superestímulos, cuyas distintas facetas conducen a la sobreexcitación del sistema nervioso humano. Esa excitación tiende a perjudicar el bienestar a largo plazo del hombre. Pero el daño no se queda ahí. Nuestro mundo social y familiar se ve rápidamente desintegrado por los excesos y la toxicidad del amor romántico. En cierto modo, el amor romántico se ha convertido en una de las mayores explotaciones anti-humanas de la biología humana que ha conocido nuestra especie.

Para comprender de dónde proviene esto, es necesario examinar sucintamente la historia del amor romántico, antiguamente llamado amor cortés, para así mostrar que en sus comienzos ya se aplicaban esos mismos elementos. Tal y como han expuesto detalladamente nuestros antepasados medievales, la literatura revela la misma neotenia exagerada, la misma exageración de la sexualidad y la misma obsesión con el control del afecto romántico.

Aunque el engaño de la neotenia lleva en funcionamiento desde el antiguo Egipto, como mínimo, con las sombras y delineadores de ojos, esa práctica se popularizó después de que los cruzados descubrieran los cosméticos que se utilizaban en Oriente Medio y los difundieran por toda Europa5. En la Edad Media, las aristócratas europeas utilizaban ampliamente los cosméticos; Francia e Italia eran los centros principales de fabricación de cosméticos, incluidos compuestos estimulantes como la belladona (que en italiano significa “mujer bella”), que hacían que los ojos pareciesen más grandes6.

De este modo, la neotenia, fabricada mediante técnicas artesanales, se convirtió en la herencia cultural de todas las generaciones de muchachas que aprendían (y siguen aprendiendo) el arte de la aplicación y la exhibición del maquillaje, particularmente en los ojos. Tales prácticas probablemente fomentaron los elogios a los ojos femeninos en la poesía trovadoresca, como los que se encuentran en la autobiografía del poeta Ulrich von Liechtenstein, titulada En servicio de las damas. Podemos leer lo siguiente:

“La dama dulce y pura sabe bien cómo reír bellamente, con sus ojos brillantes. Por ello llevo la corona de los nobles placeres, mientras sus ojos se llenan del rocío que asciende desde su puro corazón, con su risa. Inmediatamente quedo herido por Minnie.”

La vestimenta también se utilizaba para realzar la sexualidad. Sin embargo, las modas no cambiaron demasiado durante muchísimo tiempo, y su utilidad sexual no se comprendió completamente. El momento en el que se empezó a modificar con mayor frecuencia el estilo de la ropa, además de reconocerse sus múltiples formas de realzar la sexualidad, se puede situar (en opinión de los historiadores de la moda James Laver y Fernand Braudel) en Europa, aproximadamente a mediados del siglo XIV, la época en la que ciertos elementos sexualizados, como la lencería y los corsés, empezaron a cobrar fama7.

La doctora Jane Burns aporta pruebas adicionales sobre el papel de la vestimenta en el empoderamiento sexual de la mujer medieval en su libro Courtly Love Undressed: Reading Through Clothes in Medieval French Culture [“El amor cortés al desnudo: la interpretación de la cultura medieval francesa a través de la vestimenta”]8.

Como se ha mencionado antes, el truco más eficaz del amor romántico era tentar al hombre con la promesa de afecto, un objetivo que permanecía casi completamente inalcanzable. Los relatos de los trovadores dan fe de la agonía esperanzada que afligía al amante varón; el hombre permanecía en una rara especie de purgatorio, esperando algún “consuelo” de su amada.

El juego medieval del amor llegó a su máxima expresión cuando los códigos de conducta romántica animaron a jugar con los extremos de la aceptación y el rechazo. Comparemos la lista anterior de normas amorosas con la siguiente lista de El arte del amor cortés, un manual amoroso muy divulgado durante el siglo XII:

- El amor es un sufrimiento congénito.

- El que no siente celos no puede amar.

- Se sabe que el amor siempre crece o disminuye.

- El valor de un amor es proporcional a la dificultad de la conquista.

- El temor es el compañero constante del amor verdadero.

- Los celos y el deseo de amar siempre crecen al sospechar del amante.

- Poco duerme y come aquel a quien hacen sufrir sueños de amor.

- El amante siempre teme que su amor no se gane su deseo.

- Cuanto mayor sea la dificultad de intercambiar solaces, mayor será el deseo de los mismos, y mayor será el amor.

- El exceso de oportunidades para verse y para hablar disminuyen el amor9.

La obra más romántica de Shakespeare cuenta la misma historia: Julieta mantiene a su amante a medio camino entre aquí y allá, entre un vínculo estable y la vida de soltero. Aquí, Julieta le dice a su amante obediente:

“Casi es de día. Quisiera que te hubieses ido;

Pero no más lejos de lo poco

Que una niña traviesa deja volar

Al pajarillo que tiene en la mano;

Infeliz cautivo de trenzadas ligaduras,

Al que así atrae de nuevo,

Recogiendo de golpe su hilo de seda.

¡Tanto es su amor enemigo de la libertad del prisionero!”

A lo que Romeo responde, cumpliendo las expectativas del amor romántico:

“Yo quisiera ser tu pajarillo.”

En este breve paseo por la historia, hemos llegado al punto de inflexión final del artículo, donde nos hacemos la pregunta del millón de dólares de Aristóteles: la causa final. ¿Con qué fin se emplean estos superestímulos?

Muchos responderían con un tópico: que tales prácticas consiguen “éxito reproductivo”; que la mujer que las utiliza obtiene una pareja de calidad y tiene descendencia que perpetúa la especie. Pero es una explicación demasiado simple. Para empezar, hay otros objetivos en la vida humana, aparte de la reproducción: el abastecimiento de alimentos, la obtención de riqueza, las necesidades afectivas, o la gratificación narcisista de una mujer que nunca haya querido tener descendencia. Los recursos obtenidos mediante esos superestímulos cuidadosamente preparados pueden servir para otros fines.

Además, los entusiastas de la reproducción parecen no haberse dado cuenta de que esas estrategias pueden ser perjudiciales para la reproducción. No hay más que observar las relaciones fallidas por doquier, la disminución del índice de natalidad y las sociedades occidentales en decadencia; todo ello augura un futuro negro, si continuamos montados a lomos de los superestímulos que tanto nos gusta explotar.

Sin duda, al habernos centrado en la reproducción, no hemos hecho suficiente hincapié en la gratificación narcisista, aunque ésta tampoco es la motivación final. No puede haber nada más gratificante para el impulso narcisista que el ejercicio del poder (cosa que hacen la mayoría de las mujeres), y los superestímulos les otorgan un poder inmenso para ello.

Es muy posible que la satisfacción narcisista sea un rasgo profundamente socializado de la mujer moderna, pero es evidente que sólo trae beneficios a corto plazo, y que a largo plazo los resultados no son demasiado positivos. Los datos muestran que el índice de infelicidad femenina ha aumentado rápidamente en esta época en la que la mujer “lo tiene todo”.

En resumen, el ginocentrismo extremo en el que vivimos hoy en día es una aberración, un monstruo de Frankenstein que, en cierto modo, no debería existir; por lo menos no más que el gigantesco polluelo de cuco que crece en el nido de un pequeño pinzón. Es un fenómeno para el que nuestros sistemas no están preparados, pero continuamos atrapados en esteciclo de deseo incomprensible que lo mantiene vivo.

En resumen, el ginocentrismo extremo en el que vivimos hoy en día es una aberración, un monstruo de Frankenstein que, en cierto modo, no debería existir; por lo menos no más que el gigantesco polluelo de cuco que crece en el nido de un pequeño pinzón. Es un fenómeno para el que nuestros sistemas no están preparados, pero continuamos atrapados en esteciclo de deseo incomprensible que lo mantiene vivo.

Podría compararse con una campaña propagandística tan fuerte como las que se usaban durante las guerras mundiales, apelando a nuestros reflejos territoriales; la diferencia es que esta campaña ha estado utilizándose y perfeccionándose continuamente desde hace 900 años.

Sea cual sea el impulso ginocéntrico que subyace en nuestro sistema nervioso, hoy en día se ha desarrollado exageradamente, y continuamos desarrollando mediante superestímulos cada vez más sofisticados. Pero si somos conscientes de ello, tal vez, sólo tal vez, podremos expulsar el huevo de cuco de nuestro nido biológico. Podemos empezar por reconocer que hemos estado hipnotizados, y tomar la decisión de no volver a consentirlo.

Es tan sencillo como dejar de ir en pos del dragón, y matarlo.

Fuentes:

[1] Artículo de Wikipedia sobre los superestímulos.

[2] Esther Vilar, El varón domado, (1971).

[9] Andreas Capellanus: The Art of Courtly Love[El arte del amor cortés] (republicado en 1990). El manual amoroso de Capellanus se escribió en 1185, por petición de Marie de Champagne, hija del rey Luis VII de Francia y de Leonor de Aquitania.

Foto de cuco por vladlen 666 – Obra propia, CCO.

http://www.avoiceformen.com/gynocentrism/the-supersizing-of-gynocentrism/

This message is now so widespread that animal-training techniques are being redeployed by women who wish to control their man’s attachment needs. In

This message is now so widespread that animal-training techniques are being redeployed by women who wish to control their man’s attachment needs. In  ivos.

ivos.