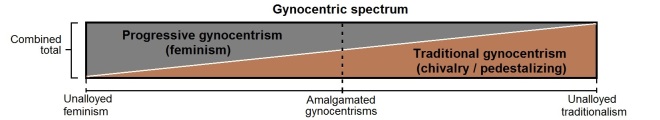

Since late in the nineteenth century, learned scholars have intensely and earnestly deliberated various historical and technical issues associated with medieval European poésie lyrique and amour courtois. This deliberation, though courteous, has been heated and pointed. Scholarly reputations have risen and fallen in the verbal battles. Just as in war generally, almost all the persons fighting in this field of medieval scholarship have been men. Consistent with the gynocentrism typical of primates, all the leading men have glorified men’s love abjection and men’s love servitude to women.

Narrow historical and technical disputes about amour courtois have obscured broad scholarly endorsement of men’s love abjection and men’s love servitude to women. Claims about medieval European poésie lyrique have been qualified to amour courtois. The latter, however, has been identified as an anachronistic term. Fin d’amor has thus among scholars become a more reputable term for amour courtois. Being French, amour courtois is more stylish than “courtly love.” Both terms are etymologically related to being classy. Embracing the spirit of democratic equality, an elite medieval scholar coined the term “courtly experience.” That term emphasizes that amour courtois is a universal impulse:

I hold that here is a gentilezza {courtesy} which is not confined to any court or privileged class, but springs from an inherent virtù {manly excellence}; that the feelings of courtoisie are elemental, not the product of a particular chivalric nurture. In the poets’ terms, they allow even the most vilain {common} to be gentil {noble}. [1]

“Courtly experience” expressed in poetry can be a way of looking at life even for peasants rolling in the hay:

The courtly experience is the sensibility that gives birth to poetry that is courtois, to poetry of amour courtois. Such poetry may be either popular or courtly, according to the circumstances of its composition. The unity of popular and courtly love-poetry is manifest in the courtly experience, which finds expression in both. [2]

Gynocentrism is typical of primates. It hence encompasses both popular and courtly love poetry. Amour courtois has been described as “un secteur du coeur, un des aspects éternels de l’homme” {a part of the heart, one of the eternal aspects of man}.[3] Stated more literally, gynocentrism is a prevalent aspect of human societies.

The stark, oppressive anti-men gender inequality at the core of amour courtois has often been obscured. In 1896, an eminent European medievalist defined la poésie courtoise {courtly love poetry}:

What distinguishes it is conceiving of love as a cult directed toward an instance of excellence and based, like Christian love, on the infinite disproportion between merit and desire; like a necessary school of honor that makes the lover worthy and transforms commoners into nobles; like a voluntary servitude that has an ennobling power and that consists in the dignity and beauty of passionate suffering. [4]

That definition completely ignores the starkly different positions of men and women in amour courtois. The monumental work Medieval Latin and the Rise of European Love-Lyric, published in 1965, expanded upon that definition:

‘le culte d’un objet excellent’ {cult directed toward an instance of excellence}: such an attitude of the poet towards his beloved is the foundation of the courtly experience. From this arises the ‘infinite disproportion’ between lover and loved one. Yet the entire love-worship of the beloved is based on the feeling that by loving such disproportion may be lessened, the infinite gulf bridged, and a way toward union, however difficult and arduous, begun. … It is what leads to such expressions as: she whom I love is peerless throughout the world; one moment with her is worth Paradise to me; I would gladly go to Hell if she were there; her beauty is radiant as the sun; she mirrors the divine light in the world; she moves among other women like a goddess; she is worshipped by saints and angels; she herself is an angel, a goddess; she is the lover’s remedy; she is his salvation. … winning such a love is infinitely arduous, and would be impossible were it not for the lady’s grace. The value of the way is intimately related to its difficulty; therefore the lady should not take pity too easily. In any case, the lover must orient himself to an absolute love, if necessary a love unto death. [5]

In 1936, an influential medievalist declared the anti-men gender inequality of amour courtois more openly and more realistically:

Every one has heard of courtly love, and every one knows that it appears quite suddenly at the end of the eleventh century in Languedoc. … The lover is always abject. Obedience to his lady’s lightest wish, however whimsical, and silent acquiescence in her rebukes, however unjust, are the only virtues he dares to claim. There is a service of love closely modelled on the service which a feudal vassal owes to his lord. The lover is the lady’s ‘man’. He addresses her as midons, which etymologically represents not ‘my lady’ but ‘my lord’. The whole attitude has been rightly described as ‘a feudalisation of love’. [6]

The scholar rightly identified an “unmistakable continuity” in this idea of love from the Middle Ages right through to the present. Men’s love servitude to women also existed in the Roman Empire in love elegy, in the relation to between caliphs and slave girls in the early Islamic world, and probably in most human societies throughout history.[7]

Scholars have only described and interpreted amour courtois while glorifying it. The scholarly imperative should be to abolish it. Writing in 1936, an influential medievalist observed:

Even our code of etiquette, with its rule that women always have precedence, is a legacy from courtly love [8]

He, however, lamented that courtly love isn’t more prevalent:

The popular erotic literature of our own day tends rather to sheikhs and ‘Salvage Men’ and marriage by capture, while that which is in favour with our intellectuals recommends either frank animalism or the free companionship of the sexes. [9]

In Theft of History, published in 2006, the chapter “Stolen Love: European Claims to the Emotions” takes amour courtois to farce:

the associated claim that love is uniquely European has also had a number of political implications being bound up not only with the development of capitalism but also being used in the service of imperialism. There is a palace in Mérida in Yucatan, the decoration of which portrays helmeted and armoured conquistadores towering over vanquished savages, with an inscription that proclaims the conquering power of love. That emotion, fraternal rather than sexual, had been claimed by the imperialist conquerors from Europe. Love literally conquers all in the hands of the invading military. [10]

Claiming amour courtois for a time or place is no substitute for meaningful ethical judgment. Amour courtois, which has at its core the subordination of men to women, isn’t humane. Amour courtois remains far too prevalent in societies around the world. Medieval European literature, wrongly understood as the source of amour courtois, provides important resources for overcoming it. Everyone needs to be educated through careful study of Lamentationes Matheoluli, Vita Aesopi, Solomon and Marcolf, Old French fabliaux, medieval women’s love poetry, and especially Boccaccio.

Notes:

[1] Dronke (1965) p. 3. Id., p. 7, refers to “the way of acquiring the virtù that she embodies.” That feminine usage of virtù reflects Dronke’s blurring of stark sex differences in amour courtois.

[2] Id. p. 3. Id, n. 1, explains:

I speak of the courtly experience rather than, say, the courtly manner or fashion because, beyond manners and fashions, it can entail a whole way of looking at life.

Dronke doesn’t speak about how looking at life through amour courtois differs in domination and subordination between women and men.

[3] Marrou (1947) p. 89, cited in Dronke (1965) pp. ix, 46.

[4] Bédier (1896) p. 172, cited in Dronke (1965) p. 4, my translation from French. The original French text:

Ce qui lui est propre, c’est d’avoir conçu l’amour comme un culte qui s’adresse à un objet excellent et se fonde, comme l’amour chrétien, sur l’infinie disproportion du mérite au désir ; — comme une école nécessaire d’honneur, qui fait valoir l’amant et transforme les vilains en courtois ; — comme un servage volontaire qui recèle un pouvoir ennoblissant, et fait consister dans la souffrance la dignité et la beauté de la passion.

Bédier was disputing the views of his contemporary scholars Alfred Jeanroy and Gaston Paris. All are influential figures in scholarship on amour courtois. C.S. Lewis characterized amour courtois as Humility, Courtesy, Adultery, and the Religion of Love. Lewis (1936) p. 2. The three characteristics other than adultery exist together in some medieval love poetry. That has spurred marginal disputes about amour courtois.

[5] Dronke (1965) pp. 4-5, 7. In his elaboration on Bédier’s definition, Dronke treats gender difference as merely a grammatical formalism. Gender difference emerges only when Dronke moves to “such expressions as.” The subordinate, abject lover is the man (he) and the dominant, paragon of excellence is the woman (she).

[6] Lewis (1936) p. 2. The reference to “unmistakeable continuity” is id. p. 3. Id. pp. 11, 12 calls amour courtois a “new sentiment” and a “new feeling” that originated in the love poetry of the late-eleventh-century Provençal troubadours. Donke, in contrast, declares nothing new and no geographic origin for amour courtois. Dronke also regards amour courtois as not particularly associated with feudal, chivalric society. Dronke (1965) p. ix. His depiction of amour courtois is nonetheless consistent with servant / lord feudal relations.

[7] Dronke (1965), Ch. I, documents the courtly experience of amour courtois in ancient Egyptian literary love songs; medieval Byzantium popular love songs; Rusthaveli’s The Man in the Panther’s Skin, written in Georgian about 1200; in the pre-Islamic Arabic poetry of Jamil and Buthaynah, the early Islamic poetry of ibn al-Ahnaf, and the eleventh-century Persian romance Wis and Ramin; love poetry of Mozarabic Spain; refrains of medieval France and Germany; tenth-century Icelandic skaldic poetry; and medieval love poetry in the Greek-Italian dialect of Calabria.

[8] Id. pp. 3-4. Scholars have provided rationalizations for denying and reversing men’s manifest subordination in courtly love. The collapse of reason is now pervasive in medieval scholarship:

As is now generally recognized, the rhetoric of courtly love is a social discourse of coercive power, asserting the courtier’s dominance over both the female love-object and men of lesser status.

Garrison (2015) p. 323. Anti-men gender bigotry is now similarly interpreted as promoting gender equality. Moreover, as the Costa Condordia disaster made clear, men continue to be denied equal opportunity to get off sinking ships.

[9] Id. p. 1. The term “salvage” apparently is an archaic form of “savage.”

[10] Goody (2006) p. 285. These are the concluding sentences of the chapter. The non-gendered reference to military action underscores lack of concern for men’s lives.

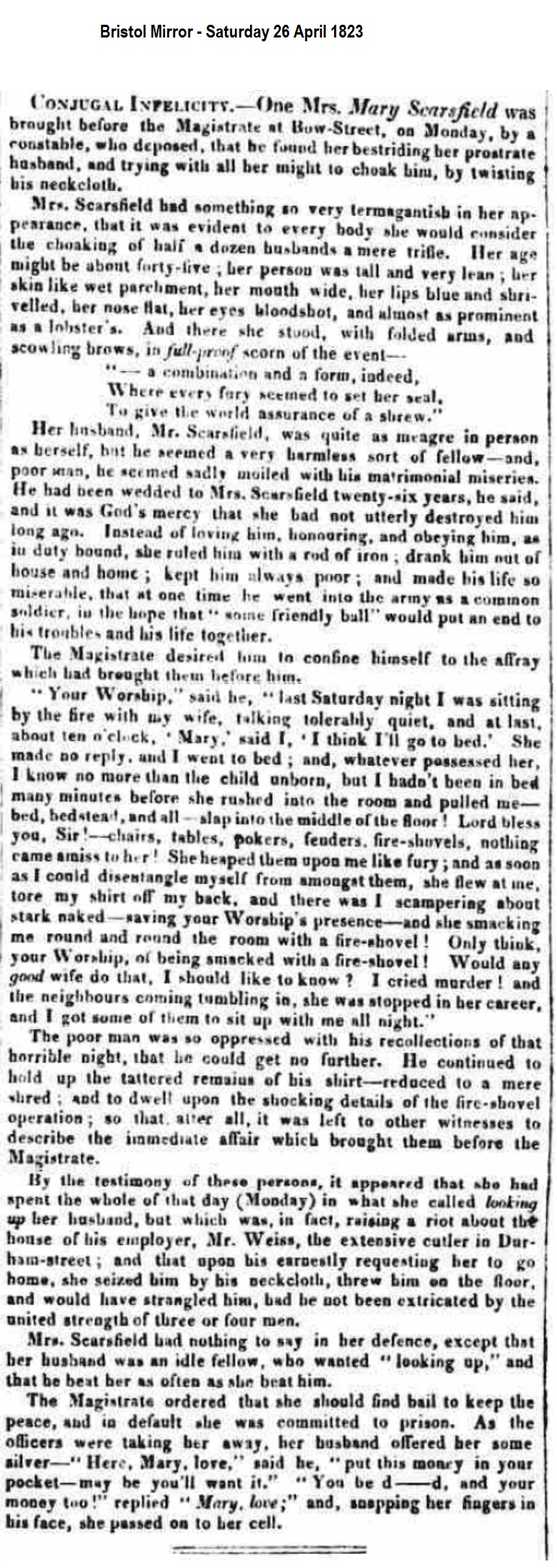

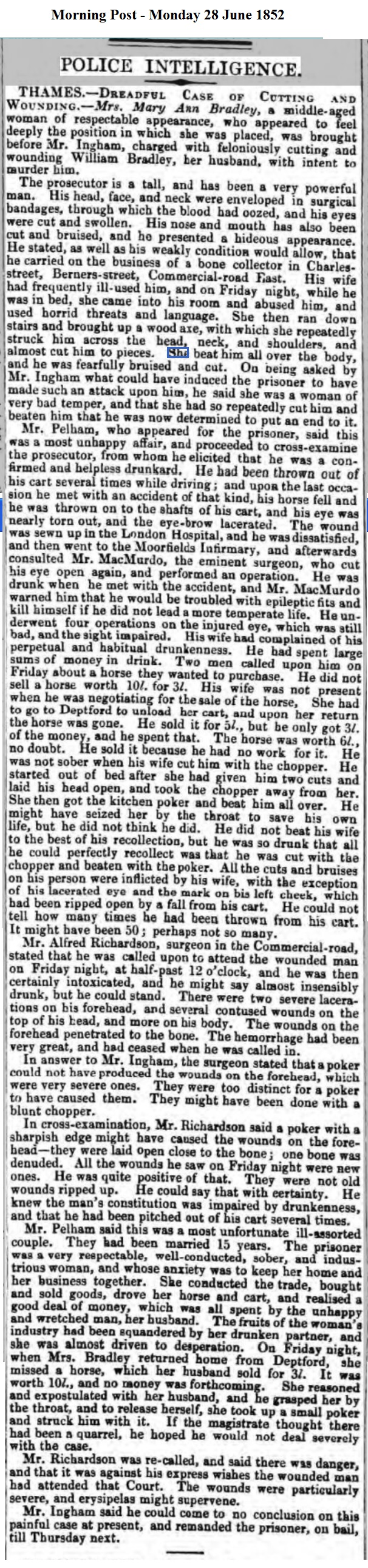

[image] Knight serving woman in amour courtois. Oil on canvas. Edmund Leighton, English, 1901. Thanks to Wikimedia Commons.

References:

Bédier, Joseph. 1896. “Les fêtes de mai et les commencemens de la poésie lyrique au moyen âge.” Revue des Deux Mondes 135: 146-72.

Dronke, Peter. 1965. Medieval Latin and the rise of European love-lyric. Vol I. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Garrison, Jennifer. 2015. “Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde and the Danger of Masculine Interiority.” The Chaucer Review. 49 (3): 320-343.

Goody, Jack. 2006. The theft of history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, C. S. 1936. The allegory of love; a study in medieval tradition. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

Marrou, Henri-Irénée. 1947. “Au dossier de l’amour courtois.” Revue du Moyen Age Latin 3: 81-89.

Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

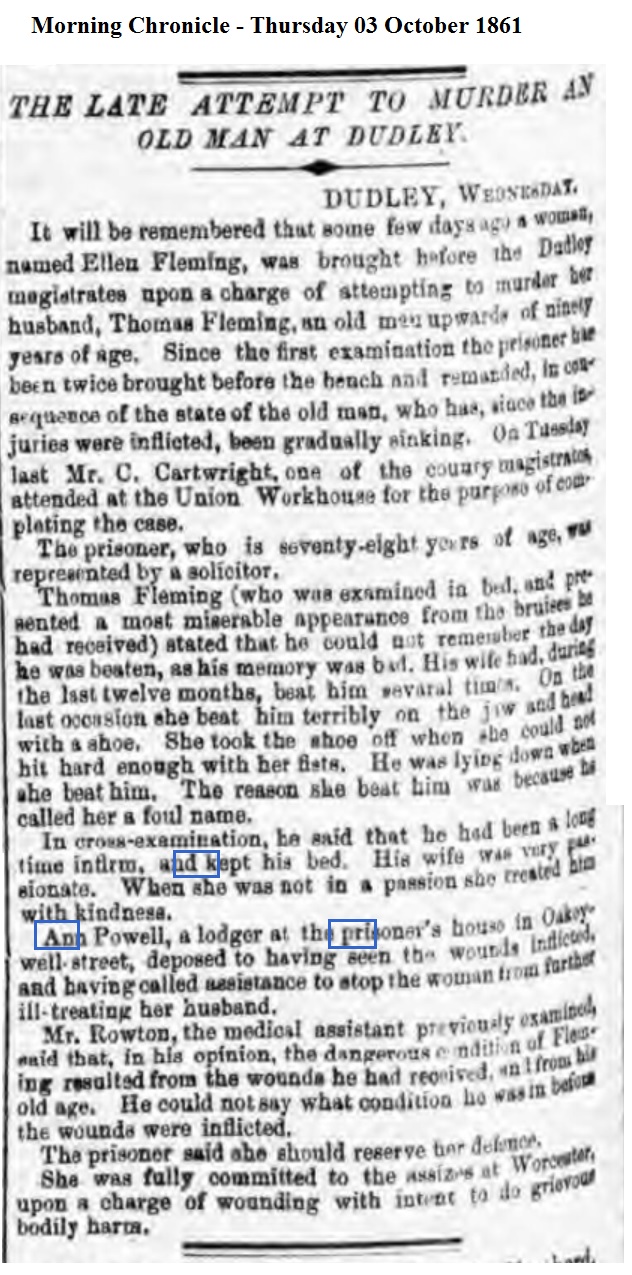

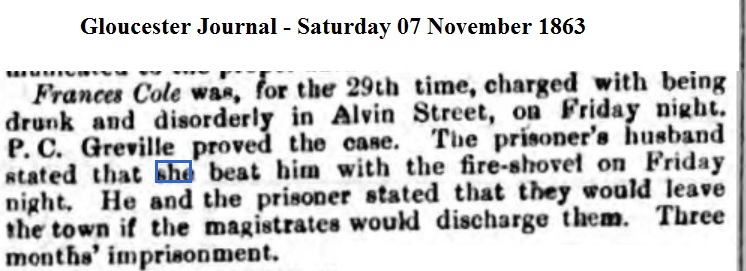

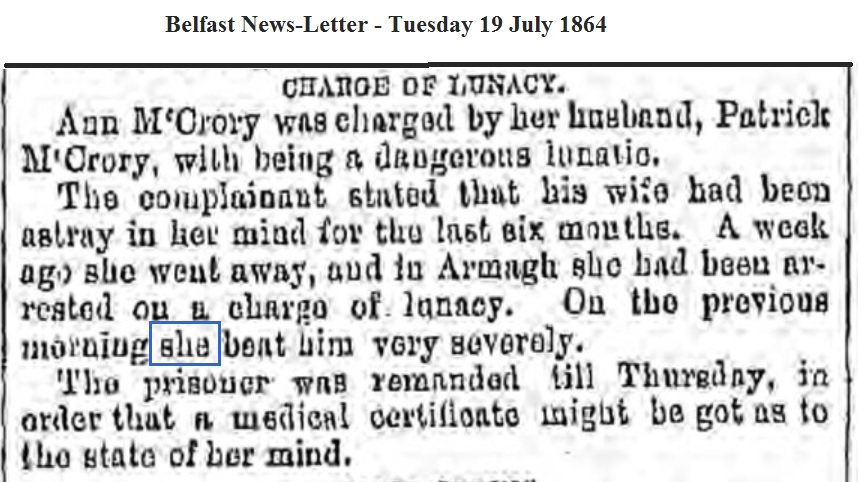

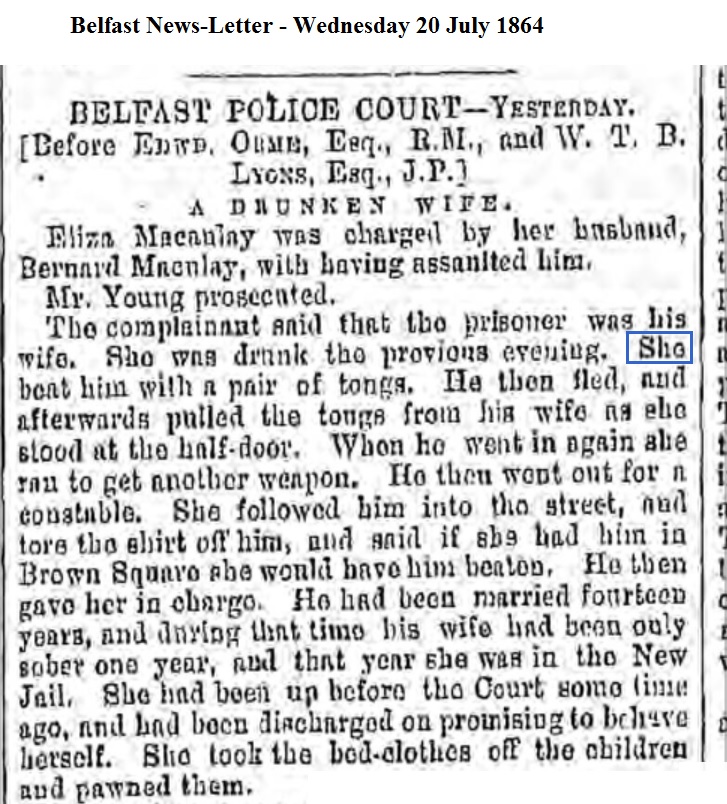

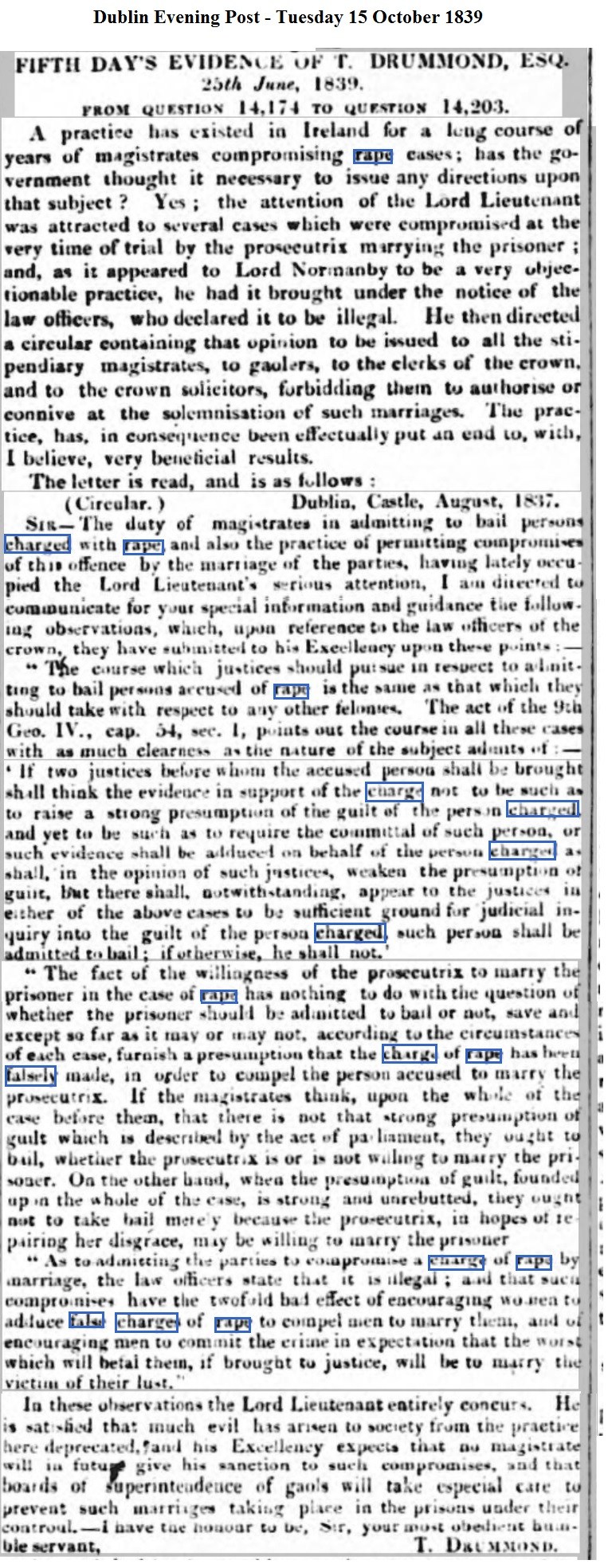

If the magistrates think, upon the whole of the case before them, that there is not a strong presumption of guilt which is described by the act of parliament, they ought to bail, whether the prosecutrix is or is not willing to marry the prisoner. On the other hand, when the presumption of guilt, founded upon the whole of the case, is strong and unrebutted, they ought not to take bail merely because the prosecutrix, in the hopes of repairing her disgrace, may be willing to marry the prisoner.

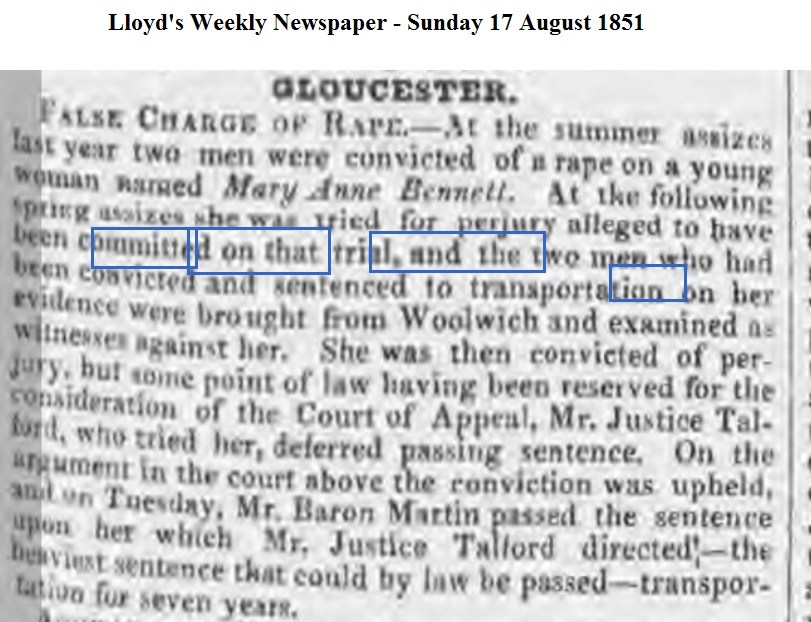

If the magistrates think, upon the whole of the case before them, that there is not a strong presumption of guilt which is described by the act of parliament, they ought to bail, whether the prosecutrix is or is not willing to marry the prisoner. On the other hand, when the presumption of guilt, founded upon the whole of the case, is strong and unrebutted, they ought not to take bail merely because the prosecutrix, in the hopes of repairing her disgrace, may be willing to marry the prisoner. She was then convicted of perjury, but some point of law having been reserved for the consideration of the Court of Appeal, Mr. Justice Talford, who tried her, deferred passing sentence. On the argument in the court above the conviction was upheld, and on Tuesday, Mr. Baron Martin passed the sentence upon her which Mr. Justice Talford directed — the heaviest sentence that could by law be passed — transportation for seven years.

She was then convicted of perjury, but some point of law having been reserved for the consideration of the Court of Appeal, Mr. Justice Talford, who tried her, deferred passing sentence. On the argument in the court above the conviction was upheld, and on Tuesday, Mr. Baron Martin passed the sentence upon her which Mr. Justice Talford directed — the heaviest sentence that could by law be passed — transportation for seven years. In the preliminary examination before the magistrate, Mr. Clarkson said that in five instances he could prove that this girl, from the age of fifteen, had made charges of this description against persons in whose houses she had been hired as a servant. There was reason to believe she had been successful in compromising some of them, and that on one occasion she had received twenty pounds.

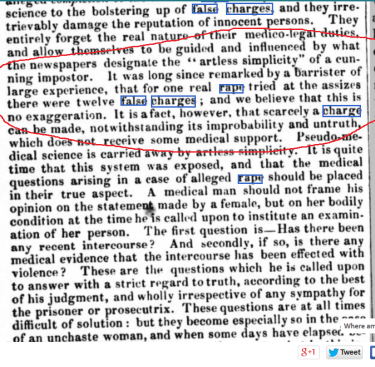

In the preliminary examination before the magistrate, Mr. Clarkson said that in five instances he could prove that this girl, from the age of fifteen, had made charges of this description against persons in whose houses she had been hired as a servant. There was reason to believe she had been successful in compromising some of them, and that on one occasion she had received twenty pounds. [Medical men] entirely forget the the real nature of their medico-legal duties, and allow themselves to be guided and influence by what the newspapers designate the “artless simplicity” of a cunning imposter. It was long since remarked by a barrister of large experience, that for one real rape tried at the assizes there were twelve false false charges; and we believe that this is no exaggeration. It is a fact, however, that scarcely a charge can be made, notwithstanding its improbability and untruth, which does not receive some medical support. Pseudo-medical science is carried away by artless simplicity.

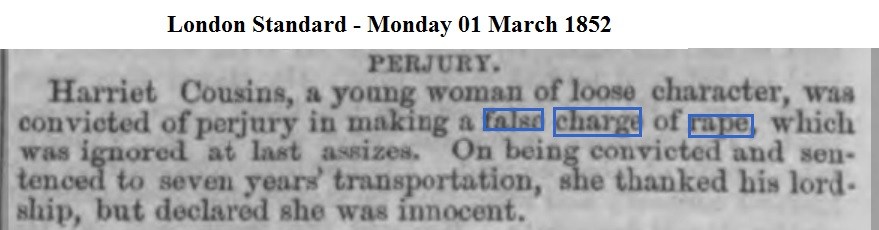

[Medical men] entirely forget the the real nature of their medico-legal duties, and allow themselves to be guided and influence by what the newspapers designate the “artless simplicity” of a cunning imposter. It was long since remarked by a barrister of large experience, that for one real rape tried at the assizes there were twelve false false charges; and we believe that this is no exaggeration. It is a fact, however, that scarcely a charge can be made, notwithstanding its improbability and untruth, which does not receive some medical support. Pseudo-medical science is carried away by artless simplicity. Harriet Cousins, a young woman of loose character, was convicted of perjury in making a false charge of rape, which was ignored at last assizes. On being convicted and sentenced to seven years transportation, she thanked his lordship, but declared she was innocent.

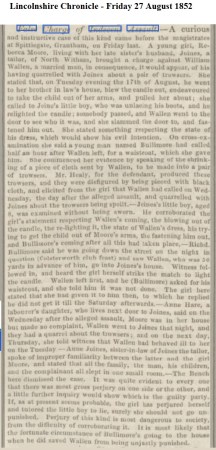

Harriet Cousins, a young woman of loose character, was convicted of perjury in making a false charge of rape, which was ignored at last assizes. On being convicted and sentenced to seven years transportation, she thanked his lordship, but declared she was innocent. A curious and instructive case of this kind came before the magistrates at Spittlegate, Grantham, on Friday last. A young girl, Rebecca moore, living with her late sister’s husband, Joines, a tailor, of North Witham, brought a charge against William Wallen, a married man, in consequence, it would appear, of him having quarrelled with Joines about a pair of trousers…

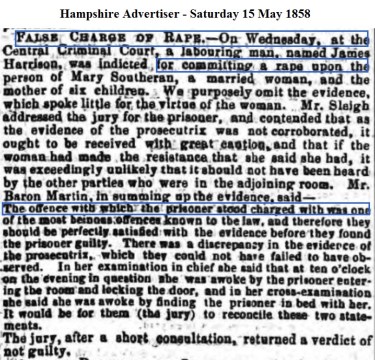

A curious and instructive case of this kind came before the magistrates at Spittlegate, Grantham, on Friday last. A young girl, Rebecca moore, living with her late sister’s husband, Joines, a tailor, of North Witham, brought a charge against William Wallen, a married man, in consequence, it would appear, of him having quarrelled with Joines about a pair of trousers… Baron martin, in summing up the evidence said:- “The offence with which the prisoner stood charged with was one of the most heinous offences known to the law, and therefore they should be perfectly satisfied with the evidence before they found the prisoner guilty. There was a discrepancy in the evidence of the prosecutrix, which they could not have failed to have observed. In her examination in chief she said that at ten o’clock on the evening in question, she was awoke by the prisoner entering the room and locking the door, and in her cross-examination she said she was awoke by finding the prisoner in bed with her. It would be for them (the jury) to reconcile these two statements. The jury, after a short consultation, returned a verdict of not guilty.

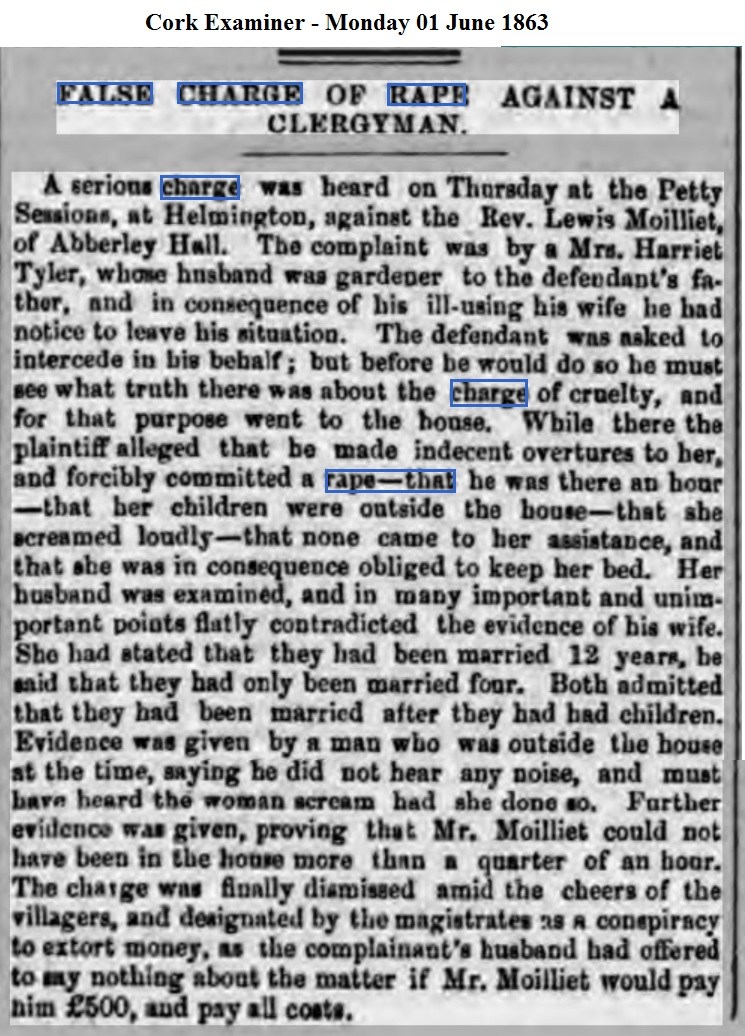

Baron martin, in summing up the evidence said:- “The offence with which the prisoner stood charged with was one of the most heinous offences known to the law, and therefore they should be perfectly satisfied with the evidence before they found the prisoner guilty. There was a discrepancy in the evidence of the prosecutrix, which they could not have failed to have observed. In her examination in chief she said that at ten o’clock on the evening in question, she was awoke by the prisoner entering the room and locking the door, and in her cross-examination she said she was awoke by finding the prisoner in bed with her. It would be for them (the jury) to reconcile these two statements. The jury, after a short consultation, returned a verdict of not guilty. Her husband was examined and in many important and unimportant points flatly contradicted the evidence of his wife. She had stated they had been married 12 years, he said they had only been married four. Both admitted they had been married after they had had children. Evidence was given by a man who was outside the house at the time, saying he did not hear any noise, and must have heard the woman scream had she done so. Further evidence was given, proving that Mr. Moilliet could not have been in the house more than a quarter of an hour.

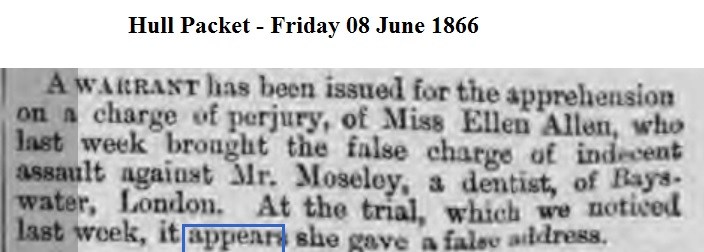

Her husband was examined and in many important and unimportant points flatly contradicted the evidence of his wife. She had stated they had been married 12 years, he said they had only been married four. Both admitted they had been married after they had had children. Evidence was given by a man who was outside the house at the time, saying he did not hear any noise, and must have heard the woman scream had she done so. Further evidence was given, proving that Mr. Moilliet could not have been in the house more than a quarter of an hour. A Warrant has been issued for the apprehension on a charge of perjury, of Miss Ellen Allen, who last week brought the false charge of indecent assault against Mr. Moseley, a dentist, of Bayswater, London. At the trial, which we noticed last week, it appears she gave a false address.

A Warrant has been issued for the apprehension on a charge of perjury, of Miss Ellen Allen, who last week brought the false charge of indecent assault against Mr. Moseley, a dentist, of Bayswater, London. At the trial, which we noticed last week, it appears she gave a false address. The offence was one of the most serious which could be advanced against any person, and if it had been successfully established in this instance, it would have unquestionably involved the utter ruin of an entirely innocent man. When the charge was made with the view of extorting money, and when that charge was deliberately persisted in before the magistrate, the court felt bound to pass a severe sentence, and yet the lightest which for such an abominable crime could be passed — namely, that the prisoner be kept in penal servitude for a term of five years — no one will think the term too severe.

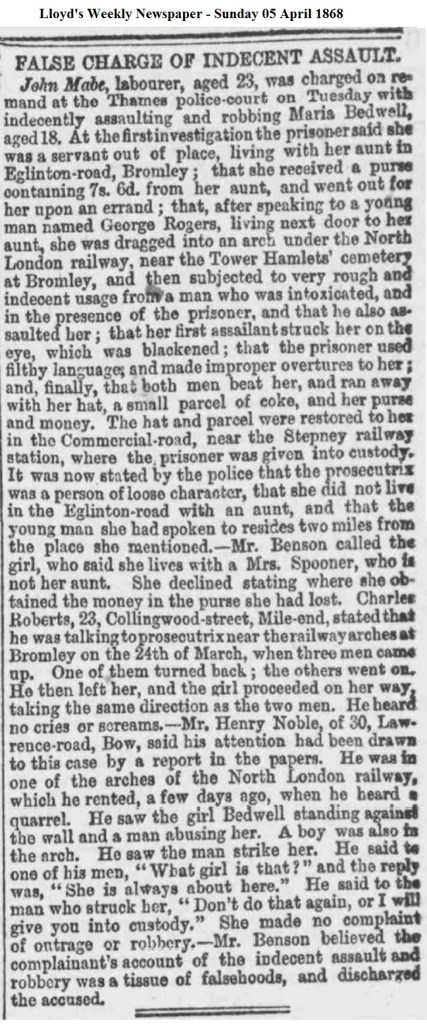

The offence was one of the most serious which could be advanced against any person, and if it had been successfully established in this instance, it would have unquestionably involved the utter ruin of an entirely innocent man. When the charge was made with the view of extorting money, and when that charge was deliberately persisted in before the magistrate, the court felt bound to pass a severe sentence, and yet the lightest which for such an abominable crime could be passed — namely, that the prisoner be kept in penal servitude for a term of five years — no one will think the term too severe. John Mabe, labourer, aged 23, was charged on remand at the Thames Police Court on Tuesday with indecently assaulting and robbing Maria Bedwell, aged 18. At first investigation the prisoner said she was a servant out of place, living with her aunt in Eglinton-road, Bromley, that she received a purse containing 7s. 3d. from her aunt, and went out for her upon an errand…. she was dragged into an arch under the North London railway and subjected to very rough and indecent usage from a man who was intoxicated, and in the presence of the prisoner and that he also assaulted her…

John Mabe, labourer, aged 23, was charged on remand at the Thames Police Court on Tuesday with indecently assaulting and robbing Maria Bedwell, aged 18. At first investigation the prisoner said she was a servant out of place, living with her aunt in Eglinton-road, Bromley, that she received a purse containing 7s. 3d. from her aunt, and went out for her upon an errand…. she was dragged into an arch under the North London railway and subjected to very rough and indecent usage from a man who was intoxicated, and in the presence of the prisoner and that he also assaulted her… On Thursday James Berwick, proprietor of the Lorrimore Arms Tavern, Walworth, surrendered his bail at the Surrey sessions, to answer to an indictment charging him with indecently assaulting Miss Kate Gander, about 17 years of age….

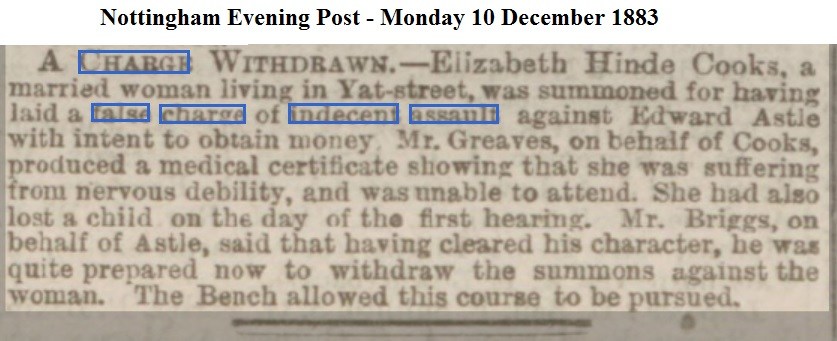

On Thursday James Berwick, proprietor of the Lorrimore Arms Tavern, Walworth, surrendered his bail at the Surrey sessions, to answer to an indictment charging him with indecently assaulting Miss Kate Gander, about 17 years of age…. Elizabeth Hinde Cooks, a married woman living in Yat-street, was summoned for having laid a false charge of indecent assault against Edward Astle with intent to obtain money. Mr Greaves, on behalf of Cooks, produced a medical certificate showing that she was suffering from nervous debility, and was unable to attend. She had also lost a child on the day of the first hearing. Mr. Briggs, on behalf of Astle, said that having cleared his character, he was quite prepared now to withdraw the summons against the woman. The Bench allowed this course to be pursued.

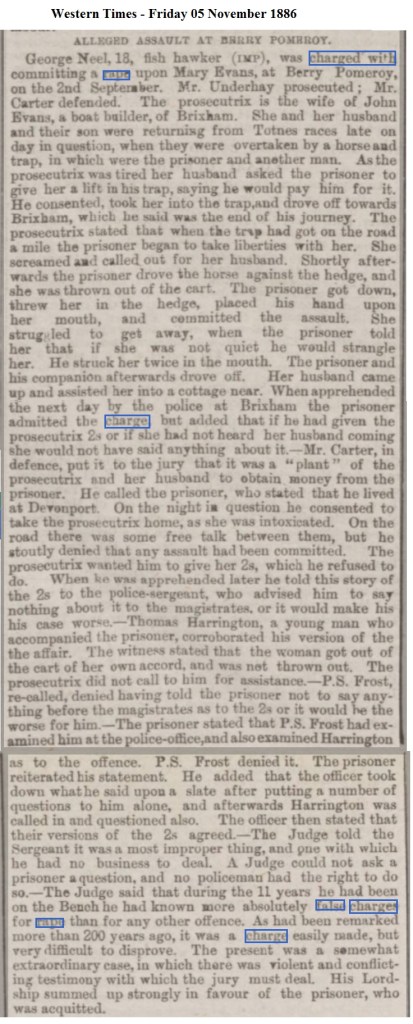

Elizabeth Hinde Cooks, a married woman living in Yat-street, was summoned for having laid a false charge of indecent assault against Edward Astle with intent to obtain money. Mr Greaves, on behalf of Cooks, produced a medical certificate showing that she was suffering from nervous debility, and was unable to attend. She had also lost a child on the day of the first hearing. Mr. Briggs, on behalf of Astle, said that having cleared his character, he was quite prepared now to withdraw the summons against the woman. The Bench allowed this course to be pursued. George Neel, 18, fish hawker, was charged with committing a rape upon Mary Evans, at Berry Pomeroy, on the 2nd of September. Mr. Underhay prosecuted; Mr. Carter defended. The prosecutrix is the wife of John Evans, a boat builder, of Brixham…

George Neel, 18, fish hawker, was charged with committing a rape upon Mary Evans, at Berry Pomeroy, on the 2nd of September. Mr. Underhay prosecuted; Mr. Carter defended. The prosecutrix is the wife of John Evans, a boat builder, of Brixham…