|

Gynocentrism (n.) refers to a dominant focus on women’s needs and wants relative to men’s needs and wants. This can happen in the context of cultural conventions, social institutions, political policies, and in gendered relationships.1 |

Introduction

Cultural gynocentrism emerged in Medieval Europe during a time of profound cross-cultural exchange and shifting gender customs. From the 11th century onward, European society absorbed influences ranging from Arabic love poetry to aristocratic courtship trends, alongside the rise of the Marian cult. This climate was further shaped by figures such as Eleanor of Aquitaine and her daughter Marie who transformed the ideal of chivalry into a code of male service to women —a tradition now known as courtly love.

Courtly love was popularized through the work of troubadours, minstrels, playwrights, and by commissioned romance writers whose stories laid down a model of romantic fiction that remains the most commercially successful genre of literature to this day. That confluence of factors generated the conventions that continue to drive gynocentric practices to the present.

Gynocentrism as a cultural phenomenon

The primary elements of gynocentric culture, as we experience it today, are derived from practices originating in medieval society such as feudalism, chivalry and courtly love. These traditions continue to shape contemporary society in subtle but enduring ways. In this context, various scholars and writers have described gynocentric patterns as a form of “sexual feudalism.”

For example, in 1600, the Italian writer Lucrezia Marinella observed that women of lower social classes were often treated as superiors, while men served them like knightly retainers and beasts of burden. Similarly, Modesta Pozzo, writing in 1590, remarked:

“Don’t we see that men’s rightful task is to go out to work and wear themselves out trying to accumulate wealth, as though they were our factors or stewards, so that we can remain at home like the lady of the house directing their work and enjoying the profit of their labors? That, if you like, is the reason why men are naturally stronger and more robust than us — they need to be, so they can put up with the hard labor they must endure in our service.”2

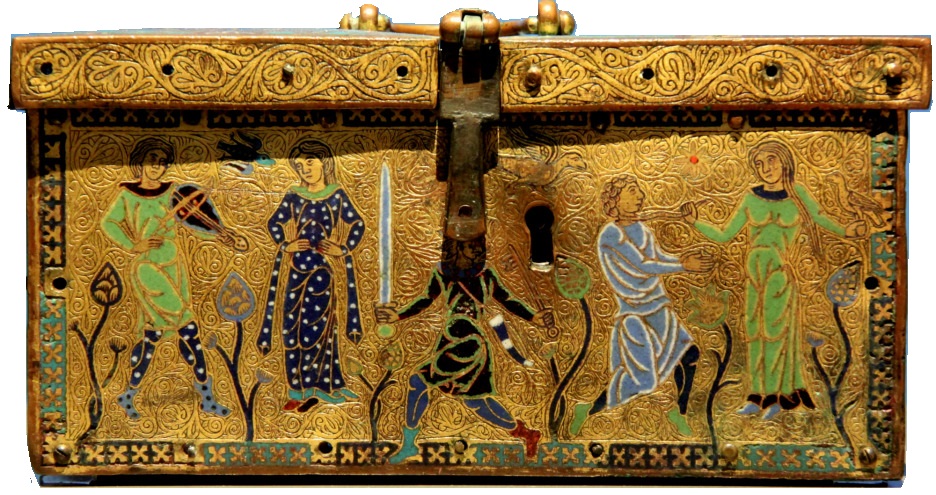

The golden casket at the head of this page depicting scenes of servile behaviour toward women were typical of courtly love culture of the Middle Ages. Such objects were given to women as gifts by men seeking to impress. Note the woman standing with hands on hips in a position of authority, and the man being led around by a neck halter, his hands clasped in a position of subservience.

It’s clear that much of what we today call gynocentrism was invented in this early period, where the feudal template was employed as the basis for a new model for love in which men would play the role of a vassal to women who assumed the role of an idealized Lord.

C.S. Lewis, in the middle of the 20th Century, referred to this historical revolution as “the feudalisation of love,” and stated that it has left no corner of our ethics, our imagination, or our daily life untouched. “Compared with this revolution,” states Lewis, “the Renaissance is a mere ripple on the surface of literature.”3 Lewis further states;

“Everyone has heard of courtly love, and everyone knows it appeared quite suddenly at the end of the eleventh century at Languedoc. The sentiment, of course, is love, but love of a highly specialized sort, whose characteristics may be enumerated as Humility, Courtesy, Adultery and the Religion of Love. The lover is always abject. Obedience to his lady’s lightest wish, however whimsical, and silent acquiescence in her rebukes, however unjust, are the only virtues he dares to claim. Here is a service of love closely modelled on the service which a feudal vassal owes to his lord. The lover is the lady’s ‘man’. He addresses her as midons, which etymologically represents not ‘my lady’ but ‘my lord’. The whole attitude has been rightly described as ‘a feudalisation of love’. This solemn amatory ritual is felt to be part and parcel of the courtly life.” 4

With the advent of (initially courtly) women being elevated to the position of ‘Lord’ in intimate relationships, and with this general sentiment diffusing to the masses and across much of the world today, we are justified in talking of a gynocentric cultural complex that affects, among other things, relationships between men and women. Further, unless evidence of widespread gynocentric culture can be found prior to the Middle Ages, then gynocentrism is approximately 1000 years old. In order to determine if this thesis is valid we need to look further at what we mean by “gynocentrism”.

The term gynocentrism has been in circulation since the 1800’s, with the general definition being “focused on women; concerned with only women.”5 From this definition we see that gynocentrism could refer to any female-centered practice, or to a single gynocentric act carried out by one individual. There is nothing inherently wrong with a gynocentric act (eg. celebrating Mother’s Day) , or for that matter an androcentric act (celebrating Father’s Day). However when a given act becomes instituted in the culture to the exclusion of other acts we are then dealing with a hegemonic custom — i.e. such is the relationship custom of elevating women to the position of men’s social, moral or spiritual superiors.

Author of Gynocentrism Theory Adam Kostakis has attempted to expand the definition of gynocentrism to refer to “male sacrifice for the benefit of women” and “the deference of men to women,” and he concludes; “Gynocentrism, whether it went by the name honor, nobility, chivalry, or feminism, its essence has gone unchanged. It remains a peculiarly male duty to help the women onto the lifeboats, while the men themselves face a certain and icy death.”6

While we can agree with Kostakis’ descriptions of assumed male duty, the phrase gynocentric culture more accurately carries his intention than gynocentrism alone. Thus when used alone in the context of this website gynocentrism refers to part or all of gynocentric culture, which is defined here as any culture instituting rules for gender relationships that benefit females at the expense of males across a broad range of measures.

At the base of gynocentric culture lies the practice of enforced male sacrifice for the benefit of women. If we accept this definition we must look back and ask whether male sacrifices throughout history were always made for the sake women, or alternatively for the sake of some other primary goal? For instance, when men went to die in vast numbers in wars, was it for women, or was it rather for Man, King, God and Country? If the latter we cannot then claim that this was a result of some intentional gynocentric culture, at least not in the way I have defined it here. If the sacrifice isn’t intended directly for the benefit women, even if women were occasional beneficiaries of male sacrifice, then we are not dealing with gynocentric culture.

Male utility and disposability strictly “for the benefit of women” comes in strongly only after the advent of the 12th century gender revolution in Europe – a revolution that delivered us terms like gallantry, chivalry, chivalric love, courtesy, damsels, romance and so on. From that period onward gynocentric practices grew exponentially, culminating in the demands of today’s feminist movement. In sum, gynocentrism (ie. gynocentric culture) was a patchy phenomenon at best before the middle ages, after which it became ubiquitous.

With this in mind it makes little sense to talk of gynocentric culture starting with the industrial revolution a mere 200 years ago (or 100 or even 30 yrs ago), or of it being two million years old as some would argue. We are not only fighting two million years of genetic programming; our culturally constructed problem of gender inequity is much simpler to pinpoint and to potentially reverse. All we need do is look at the circumstances under which gynocentric culture first began to flourish and attempt to reverse those circumstances. Specifically, that means rejecting the illusions of romantic love (feudalised love), along with the practices of misandry, male shaming and servitude that ultimately support it.

La Querelle des Femmes, and advocacy for women

The Querelle des Femmes translates as the “quarrel about women” and amounts to what we might today call a gender-war. The querelle had its beginning in twelfth century Europe and finds its culmination in the feminist-driven ideology of today (though some authors claim, unconvincingly, that the querelle came to an end in the 1700s).

The basic theme of the centuries-long quarrel revolved, and continues to revolve, around advocacy for the rights, power and status of women, and thus Querelle des Femmes serves as the originating title for gynocentric discourse.

To place the above events into a coherent timeline, chivalric servitude toward women was elaborated and given patronage first under the reign of Eleanor of Aquitaine (1137-1152) and instituted culturally throughout Europe over the subsequent 200 year period. After becoming thus entrenched on European soil there arose the Querelle des Femmes which refers to the advocacy culture that arose for protecting, perpetuating and increasing female power in relation to men that continues, in an unbroken tradition, in the efforts of contemporary feminism.7

Writings from the Middle Ages forward are full of testaments about men attempting to adapt to the feudalisation of love and the serving of women, along with the emotional agony, shame and sometimes physical violence they suffered in the process. Gynocentric chivalry and the associated querelle have not received much elaboration in men’s studies courses to-date, but with the emergence of new manuscripts and quality English translations it may be profitable to begin blazing this trail.8

References

1. Wright, P., What’s in a suffix? taking a closer look at the word gyno–centrism

2. Modesta Pozzo, The Worth of Women: their Nobility and Superiority to Men

3. C.S. Lewis, Friendship, chapter in The Four Loves, HarperCollins, 1960

4. C.S. Lewis, The Allegory of Love, Oxford University Press, 1936

5. Dictionary.com – Gynocentric

6. Adam Kostakis, Gynocentrism Theory – (Published online, 2011). Although Kostakis assumes gynocentrism has been around throughout recorded history, he singles out the Middle Ages for comment: “There is an enormous amount of continuity between the chivalric class code which arose in the Middle Ages and modern feminism… One could say that they are the same entity, which now exists in a more mature form – certainly, we are not dealing with two separate creatures.”

7. Joan Kelly, Early Feminist Theory and the Querelle des Femmes (1982), reprinted in Women, History and Theory, UCP (1984)

8. The New Male Studies Journal has published thoughtful articles touching on the history and influence of chivalry in the lives of males.